In the pantheon of modern art, few names shine as brightly as Keith Haring. An artist whose work transcended the conventional boundaries of gallery spaces, Haring’s art was as much a political statement as it was a visual spectacle. Born in 1958, Haring’s career was meteoric yet tragically brief, his life cut short in 1990 due to complications from AIDS. However, in his short time, he left an indelible mark on the art world and popular culture.

Haring’s art is instantly recognisable – marked by its bold lines, vivid colours, and dynamic figures. His work was deeply embedded in the social movements and street culture of 1980s New York, reflecting issues ranging from AIDS awareness to apartheid, and the perils of drug addiction. His imagery, though seemingly simple, is layered with complex symbolism and powerful messages. It’s this fusion of accessibility and depth that has made Haring’s work resonate with a wide audience.

This article explores a selection of Keith Haring’s most significant artworks, each a testament to his unique style and enduring influence. From the iconic ‘Radiant Baby’ to the politically charged ‘Crack is Wack’ mural, Haring’s legacy is a rich tapestry of visual activism and artistic genius. Through these works, we delve into the heart of a man who believed art should be for everyone, a visionary who painted not just on canvases but on the very fabric of society.

Table of Contents

Keith Haring’s Artistic Legacy: A Journey Through His Iconic Creations

Explore the dynamic and influential world of Keith Haring, where bold lines and vivid symbols converge to form a legacy of artistic genius and social commentary.

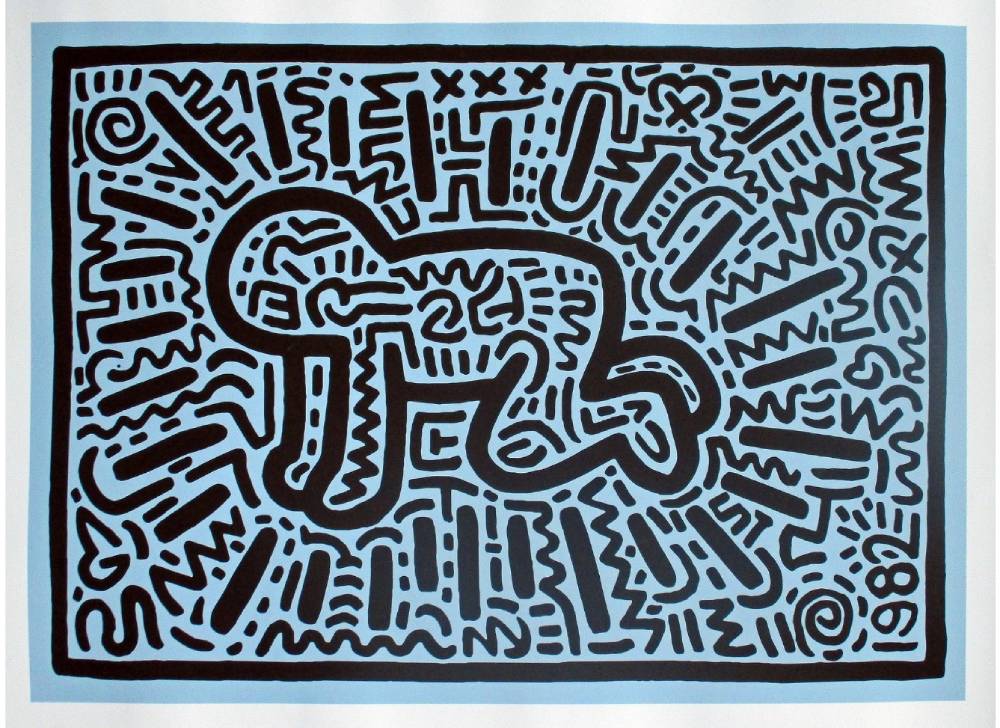

Radiant Baby (1982)

The artwork titled “Radiant Baby” from 1982 is one of Keith Haring’s most iconic images. It features a simplistic, bold outline of a crawling baby, emitting rays of light or energy that signify life and purity. The use of clear, unambiguous lines and the radiant aura around the figure typify Haring’s style, while also capturing a universal symbol of hope and the future.

This work is part of Haring’s broader effort to create art that speaks to a wide audience, using imagery that could be understood by people regardless of language or literacy. The “Radiant Baby” has been interpreted as a symbol of innocence, potential, and new beginnings, resonating deeply with many as an emblem of Haring’s optimistic and life-affirming outlook. It’s a motif that Haring revisited throughout his career, embodying his belief in art as a force for societal good and change.

The fact that “Radiant Baby” was created in the early 1980s, a period marked by rapid social change and the onset of the AIDS crisis, adds layers of interpretation to the image. It stands as a beacon of joy and energy in the face of challenging times, much like Haring’s own role as an activist and artist before his untimely death in 1990.

Source: artsy.net

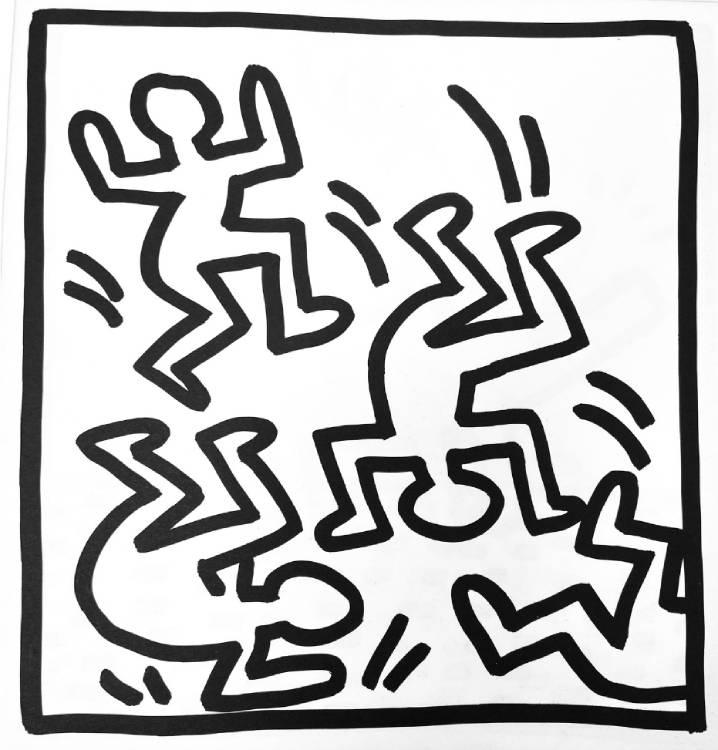

Untitled (1982) – Dancing Figures

Keith Haring’s “Untitled (1982) – Dancing Figures” is an exuberant representation of movement and energy, a theme commonly explored throughout his work. This piece, distinct for its clean, black lines against a stark white background, depicts a group of figures in a state of dynamic motion. The characters are rendered in what has become Haring’s signature style: a bold, cartoonish outline that conveys a sense of life and vibrancy.

The way the figures interlock and interact with one another on the canvas suggests a dance, a communal celebration, or perhaps a more profound connection between human beings. The dance is a primal, universal language, and here Haring taps into that collective consciousness, capturing the joy and rhythm of life itself.

Created in the early 1980s, a time when Haring was actively involved in the vibrant street culture of New York, this piece resonates with the beat of the city—its nightlife, its pulse, its people. It’s a visual symphony that speaks to the heart of Haring’s artistic mission: art for the people, art as an accessible language, art that moves, unites, and uplifts.

The artwork can be seen as a reflection of Haring’s own life philosophy—one of activism, of engagement, and of the sheer joy of creation. Even without the use of color, which Haring often employed to striking effect, “Untitled (1982) – Dancing Figures” is full of life, a testament to the power of shape and form to communicate deep human emotions and connections.

Source: artsy.net

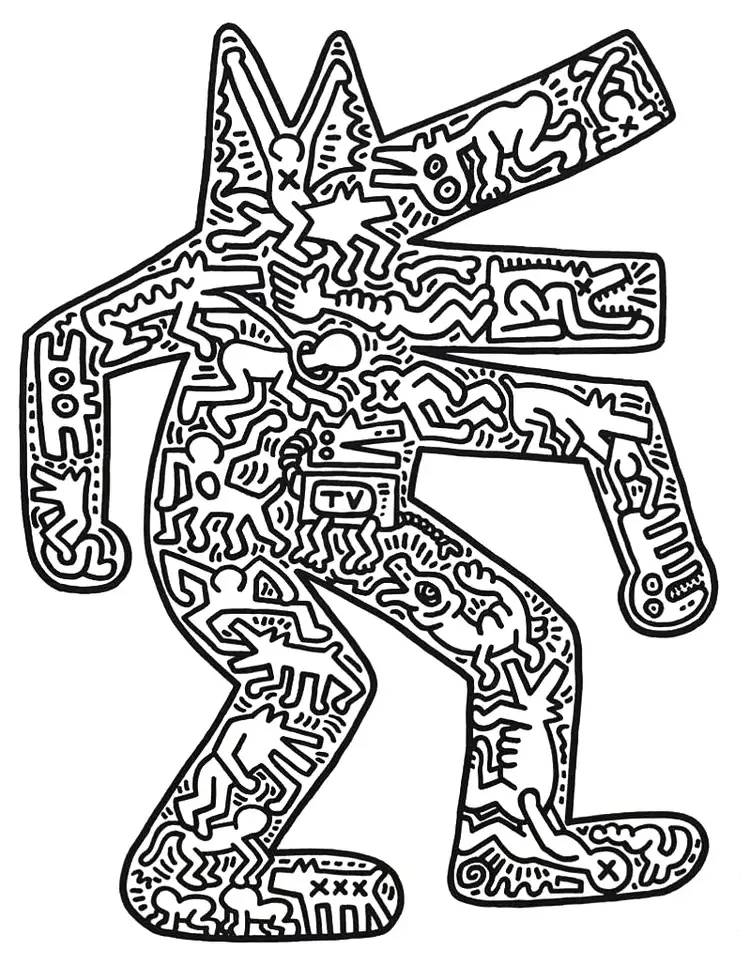

Dog (1985)

Throughout his career, Keith Haring was driven by a vision to develop a new visual language, one akin to ‘contemporary hieroglyphics’, that was accessible and resonated with a broad spectrum of people. Intriguingly, Haring’s depiction of the Dog in his 1985 artwork echoes the imagery of Anubis, the ancient Egyptian deity associated with mummification and the afterlife, often represented as a canine. This particular creation of Haring, imbued with intense themes of mortality, carnality, and chaos, serves as a potent reinterpretation of the classic hieroglyph. Through this modern lens, Haring’s Dog becomes a reflective symbol of the 1980s’ societal anxieties, most notably the HIV/AIDS crisis, channeling the era’s tensions into a powerful visual statement.

Source: haring.com

Barking Dog (1990)

Keith Haring’s “Barking Dog” is a striking example of his graphic lexicon, an image that has become synonymous with his artistic language. Through its bold, black outlines and a vivid backdrop, the artwork captures the spirit of Haring’s visual style which is both accessible and profound. The barking dog, often interpreted as a symbol of authority and societal control, is a recurring figure in Haring’s oeuvre, reflective of his commitment to activism and his commentary on power structures.

Created in the last year of Haring’s life, “Barking Dog” could be seen as an embodiment of the urgency and the fight against the socio-political issues of the time, including the AIDS crisis which Haring was personally affected by. The simplicity of the form, along with its open mouth and projecting lines, suggests a message being broadcasted, a call to attention, or a warning—consistent with Haring’s use of art as a communicative tool to raise awareness.

The artwork’s resonance is heightened by its stark contrast and the immediacy of its message, a hallmark of Haring’s work that has allowed it to remain relevant and impactful over the years. The “Barking Dog” is not just a representation but an active participant in Haring’s visual discourse on life, society, and the ongoing dialogue between power and the public.

Source: myartbroker.com

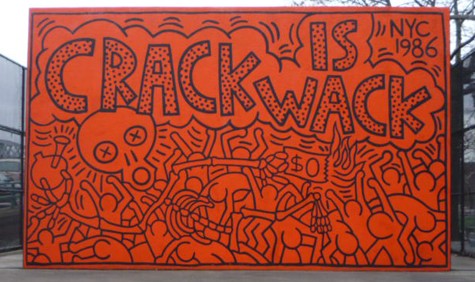

Crack is Wack (1986)

Keith Haring’s “Crack is Wack” is a profound mural that encapsulates the essence of public art as a tool for community engagement and activism. Created in 1986, this piece is a fiery tableau set against a vibrant orange backdrop, featuring Haring’s characteristic bold lines and kinetic figures. Located on a handball court along New York City’s FDR Drive, the mural became a beacon of Haring’s concern for social issues, specifically the crack cocaine epidemic that was ravaging communities at the time.

The mural’s striking imagery, dominated by a serpentine creature amidst human figures, is an impactful visualisation of the chaos and destruction wrought by drug addiction. The message is stark and direct, with the eponymous phrase “Crack is Wack” emblazoned across the top, serving both as a warning and a rallying cry against the scourge of drugs.

As with much of Haring’s work, “Crack is Wack” stands as more than art for art’s sake, it is a historical marker, a community statement, and a piece of advocacy, all rolled into one. The mural’s legacy continues to resonate, embodying Haring’s commitment to using his artistry for societal commentary and change.

Source: wikiart.org

Best Buddies (1990)

Keith Haring’s “Best Buddies,” created in 1990, is a screenprint that uses the simplicity of color and form to capture a powerful message of friendship and unity. This artwork features two figures, one in bold yellow and the other in a tan hue, against a calming turquoise background. The figures are illustrated in Haring’s immediately recognizable outline form, one with arms raised and the other following suit in a mirrored fashion, conveying a sense of camaraderie and support.

This piece embodies Haring’s ongoing dedication to depicting human connections and community spirit. The radiant lines emanating from the figures suggest a sense of energy or aura, perhaps indicative of the positivity that flows from close, supportive relationships. The use of wove paper for the print adds a subtle texture, complementing the flat planes of color and the clean black outlines that define Haring’s work.

“Best Buddies” continues to resonate as it encapsulates Haring’s activism, advocating for inclusivity and support networks, especially poignant given the backdrop of the AIDS crisis at the time. This work stands as a testament to the enduring nature of Haring’s art and its ability to communicate profound messages through simple, universal visuals.

The creation of “Best Buddies” in 1990 holds a particularly poignant place in Keith Haring’s oeuvre. This final print series, completed just 10 days before Haring succumbed to AIDS-related complications, is imbued with an urgency and a poignancy that transcends its surface simplicity.

Source: artsy.net

This list represents only a fraction of Keith Haring’s extensive and varied body of work. His art, often filled with lively figures and bold messages, has left a lasting impact on the world of contemporary art.

Check out the Keith Haring Foundation for more of his great artworks online.

Celebrating the Timeless Resonance of Keith Haring’s Vision

As we conclude our exploration of Keith Haring’s seminal artworks, it becomes evident that his legacy is as vibrant and relevant today as it was in the bustling streets and subways of 1980s New York. Haring’s art, transcending the constraints of time and culture, continues to speak to us with the same urgency and vitality.

Haring was not just an artist; he was a social activist, a dreamer, and a visionary. His works, characterised by bold lines, dynamic figures, and profound symbolism, were more than just visual creations; they were powerful dialogues on the pressing issues of his time. From advocating against drug addiction to fighting for equality and against apartheid, his art was his voice, a voice that still echoes loudly in contemporary struggles.

In retrospect, Haring’s contribution to the art world and society is monumental. He democratised art, took it to the streets, made it accessible, and used it as a tool for social change. By breaking down the barriers between high art and street culture, he redefined what art could be and who it could speak to.

Keith Haring’s journey, though tragically short, was a journey of impact and inspiration. As we look at his artworks, we are not just looking at vibrant images on a canvas; we are witnessing a legacy that continues to inspire artists, activists, and individuals around the world. Haring’s work reminds us that art is not just to be seen but to be felt, not just to be observed but to be lived. His spirit lives on, as luminous and compelling as ever, in every line, every colour, and every message he left behind.