Article commissioned by Hickman Design, Author – Sarah Cooper

Note to Reader: This article will be updated over time with more artists and journalists, please contact me with any suggestions of people or organisations to add.

Humans have been engaging in conflict right back to the dawn of our existence. War documentation only became popular as literacy levels increased, and there is evidence of war journalism dating right back to Ancient Greek and Roman periods.

Today, war photojournalism is more popular than ever. It’s one of the few ways for civilians to get a greater understanding of the battlefield, and since we live in the age of the internet, you can get that information almost instantly.

This is shown in the constant flow of media coming out of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war. People are uploading TikTok and YouTube videos, and images get shared across social media platforms instantly. It makes it difficult to hide or suppress any information since it’s being shared around the world in real-time.

However, it wasn’t always this way. Back when the news cycle moved more slowly war photographs and correspondents would document stories and images from the battle weeks, or even months, later.

Table of Contents

Early Forms of War Art

Before photography existed, painters would create artistic sketches, drawings, and epic works of art that showed how busy, chaotic, and brutal a battle can be, giving the public a greater understanding.

Battle of Pavia Painting

An early example of war art is the Battle of Pavia painting. While the artist is unknown, the detail of this piece of work shows two factions – the Roman Army and the French army facing off against each other during the Battle of Pavia in February 1525.

They were fighting over the region of Lombardy, in Northern Italy – the Italian army won and make up the lower left of the painting while the French are in the centre. It is thought the painting was created from eyewitness accounts of the battle and is considered an accurate portrayal of the battle.

Battle of Pavia Unknown Artist, Flemish

Goya’s The Disasters of War

Francisco Goya was one of Spain’s most important artists and printmakers, who spent ten years creating an 85-piece series called The Disasters of War from 1810 to 1820. These sketches documented the brutal Spanish War of Independence that occurred because of Napoleon Bonaparte installing his brother Joseph as Spain’s ruler after he took control of the country in 1808.

The Spanish resisted the move, and the ensuing war would later be called Spain’s bloodiest event. It spanned from 1808 to 1814, with up to 375,000 Spanish people (both military and civilians) perishing across the six years.

Goya’s series is anti-war, as the artist had a highly sceptical and critical view of war. The legacy of this work was not immediately felt, but is thought to have influenced Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dalí in the famous Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) piece from 1936 as a response to the Spanish Civil War.

Goya – Plate 3: Lo mismo (The same). A man about to cut off the head of a soldier with an axe.

Early Forms of War Photography – The Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853 – 1856) is where war photojournalism was truly born. Several photographers covered the conflict, creating a series of prints that showed people what a massive military conflict actually looked like. Paintings were great until this point, but a photo depicting actual human beings will always trump it.

Roger Fenton was a British photographer who went to Crimea in 1854 to document the conflict. At this time, photography was limited to stationary objects because of the bulky equipment involved. Fenton also refused to take pictures of dead soldiers (although we saw plenty of that later in World War One).

One photograph that Fenton took to show the desolation in the landscape of war became called The Valley of the Shadow of Death. It depicts a muddy ravine, which is covered in cannonballs. Fenton noted it was clear this valley had been the front line of fire at one point and had to move 100 feet when taking the picture to avoid current cannon fire. This picture is considered by many to be the ‘first iconic photograph of war’.

Roger Fenton (1819-69) – Valley of the Shadow of Death 23 – 23 April 1855

WW1 & WW2 War Photojournalism

In World War One, photograph technology had advanced significantly. Cameras were smaller, and images could be produced faster. Soon photographer’s were a staple on the battlefield, showing behind-the-scenes life of soldiers in trenches, the dangers of going ‘over the top’, and the aftermath of battles.

Never before had the public seen so many photos surrounding war, and the brutal photography taken during WW1 showed the world a truth not everyone will accept.

It shed light on the harsh living conditions for the soldiers who were fighting for their country.

Many artists emerged from WW1 who documented their experiences through illustrations and prints, a few are listed below:

Soon war photography succumbed to propaganda and censorship. The American’s understood how vital the portrayal of their soldiers was and banned the circulation of any photographs showing the soldiers drinking or smoking.

When WW2 began, technology had advanced even further and many of these iconic images of war are still circulated today. Not just in the images of the battlefield, but haunting pictures of Nazi concentration camps, showcasing the harsh reality of the Holocaust.

Some notable WW2 war photographers:

- Robert Capa

- Jimmy Mapham

- Joe Rosenthal

Pile of remaining bones at the Nazi concentration camp of Majdanek, the second largest death camp in Poland after Auschwitz – 1944

Modern War Photojournalism

In the years post-WW2, cameras have advanced to where everyone can take a high-quality image with a camera in their pocket. War correspondents and photographers have become respected individuals who put themselves at risk to document modern warfare.

The Bang-Bang Club

The Bang-Bang Club was a group of four photographers in South Africa who documented conflict within the country. They consisted of Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and Joãa Silva. The term ‘bang-bang’ is a colloquialism used by conflict photographers that refers to the sound of gunfire.

Unfortunately, the Bang-Bang Club was dismantled in 1994 after Oosterbrek was shot on assignment during a gunfight between the National Peacekeeping Force and African National Congress. Carter committed suicide just months later, and in 2010 Silva stepped on a land mine while working with U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan, and lost both legs.

The Bang-Bang Club is a perfect representation of the dangers in conflict photography. Every time a war photojournalist goes to work, they risk their lives to document the ongoing atrocities of war.

A book covering their exploits was released in 2001.

Other notable names and organisations covering conflicts:

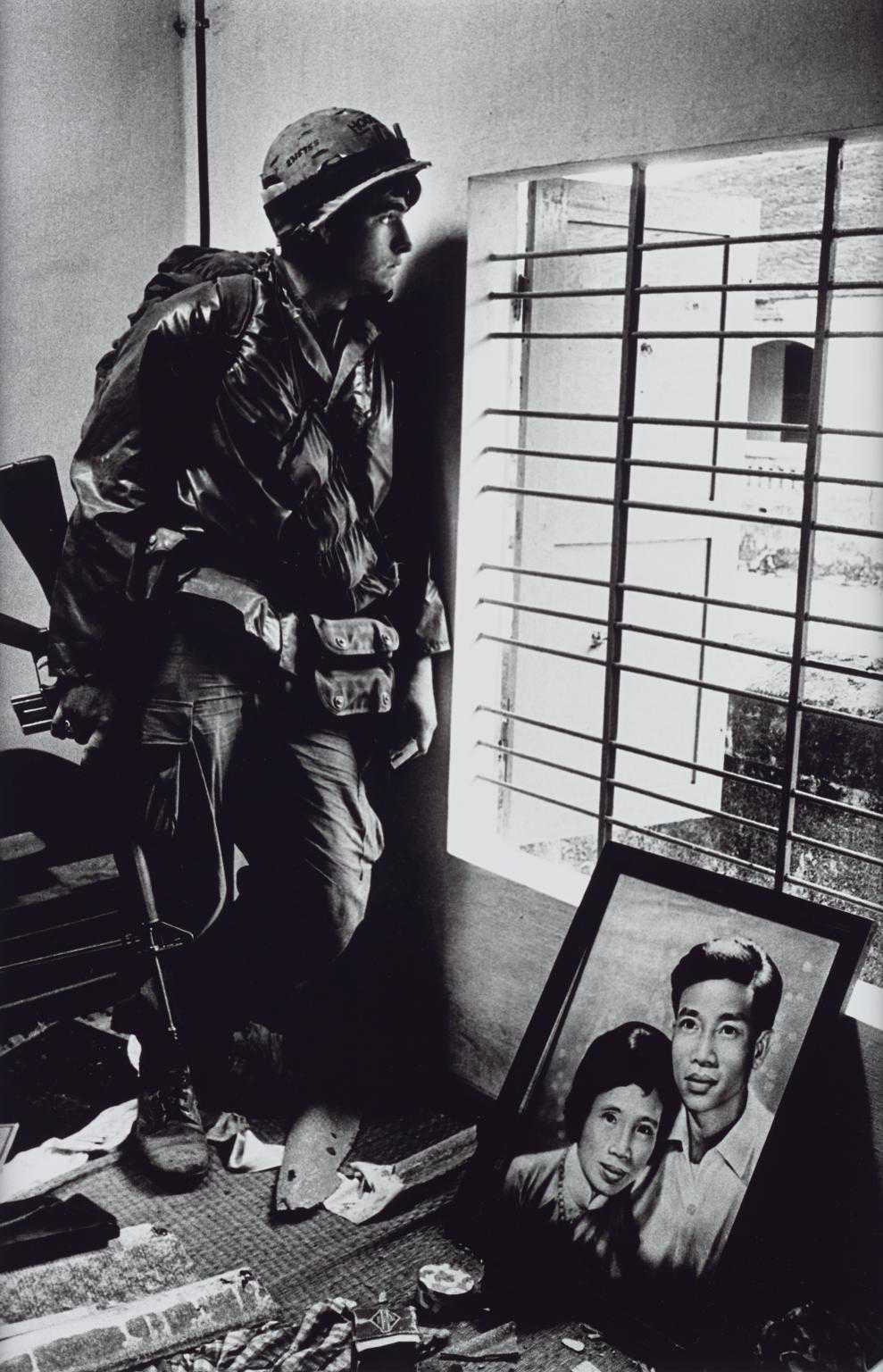

Don McCullin

Don McCullin is an award-winning British conflict photographer whose tenure at The Sunday Times Magazine from 1966 to 1984 saw him cover the Northern Irish Troubles, the war in Cyprus, Bafria, the Belgian Congo, the Lebanese Civil War, and his images of Cambodia and the Vietnam War are iconic.

During his career he’s seen plenty of danger, and was held up at knifepoint in Beirut, his Nikon camera stopped a bullet from hitting him, and he’s been gassed and wounded by a mortar shell.

His work has been exhibited in places like the Imperial War Museum and the Tate Modern, and he received a Knighthood in 2017 for his contributions to war documentation.

Don McCullin 1968 – The Battle for the City of Hue

Social Media

In the 21st century we live in a world where everyone has a camera in their pocket, which means we no longer have to rely on professional war correspondents and conflict photographers to document the battlefield. Anyone can upload a video or image to the internet, and this has become prevalent during the 21st century in the Arab Spring anti-government protests of 2010-2012, the Israel-Palestine conflict, and the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war.

There is no opportunity to suppress or censor information in the social media world, and the way we perceive images can change depending on who sent them to us. Studies have shown that people pay attention to an image more if a family or friend sent it as opposed to viewing it through a traditional media platform like a news website.

How War Reporting Has Changed Throughout History

As soon as photography developed, war paintings / art became a thing of the past. Pictures held a greater impact to the public than paint on canvas. In the last two centuries, war photography has captured the attention of the masses. Even now, we are fascinated by the videos and images coming out of the Russia-Ukrainian war. Over time, it’s evolved from photographers delivering a series of pictures after the event, to an immediate upload to the internet.

Pictures of war-torn countries have the power to shape perception, and can force us to act. Whether that means sending troops of our own, or becoming a haven for the refugees fleeing the battlefield, photography of conflict has changed public understanding of war for generations. It also provides an insight to the aftermath of war, and the consequences it has for the people affected.

It is a brutal and harsh reality of humanity.

Other Articles About War Art, Photography & Journalism

- https://history.howstuffworks.com/world-history/war-photographers.htm

- https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/articles/12-extraordinary-ww2-photographers/

- https://expertphotography.com/war-photographers/

- https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-photographers-and-filmmakers-who-captured-the-second-world-war

- https://time.com/vietnam-photos/