Article commissioned by Hickman Design, Author – Dunja Karanovic

When it comes to classical printmaking techniques, intaglio is probably as classical as it gets. Incorporating different types of techniques like etching, aquatint, drypoint, mezzotint, and their various combinations and experimental methods, intaglio is one of the most versatile methods of printmaking in the world of fine arts.

While intaglio printmaking is not really widespread outside of professional studios and art schools due to the complexity of most processes, intaglio has played an important role in making fine arts more accessible to the wider public. In this article, we will provide you with an overview of the most common techniques of intaglio printmaking, how they work, and which great masters were known to use them, as well as some additional resources and useful tutorials.

Table of Contents

Why Did We Ever Need Intaglio?

Much like how the invention of the Gutenberg printing press helped democratise the written word and brought books to people’s houses, intaglio enabled the spreading of beautiful illuminated pages and intricate drawings across Europe. The complete opposite of the much older process of relief printing (woodblock printing was perfected in Ancient China during the Tang dynasty, 618-906AD), intaglio is based on creating incisions or indentations on metal plates – most commonly steel, zinc or copper, either by physical scratching or through chemical processes.

Ink is applied so that it fills the indentations, and excess ink is removed from the plate/matrix. The deeper the incision or recess is, the darker the printed image. Because the process of ‘drawing’ on the copper and zinc plates is much more precise than cutting into woodblocks, intaglio techniques are perfect for multiplying the finer qualities of ink and pencil drawings, cross-hatched surfaces, and the subtle nuances of aquarelle and ink wash (in the case of aquatint).

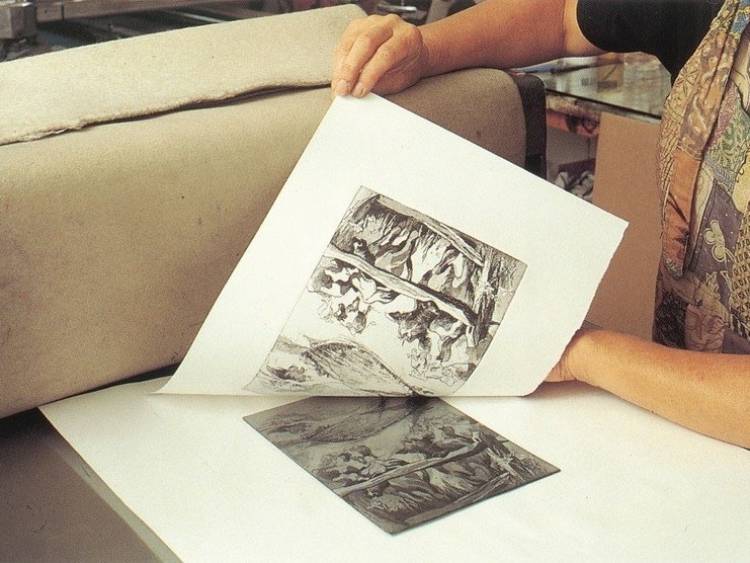

Etching Being Pulled – Source: Cut Out + Keep

The process itself had been used by goldsmiths and silver engravers before it started being applied to paper. The first printed works of intaglio go back to 15th century Germany, and the technique became increasingly popular over the next two centuries. One of the most widespread uses outside of the artworld was for banknote engraving. The artists most notable for their use of intaglio are Albrecht Durer, William Blake, Francisco Goya, Rembrandt Van Rijn, M. C. Escher, Kathe Kollwitz, Giorgio Morandi, and Pablo Picasso. Out of the wide family of intaglio techniques, engraving was the first to be discovered.

Engraving

Unlike most intaglio techniques, engraving is a mechanical process – it does not require any chemical etching. Incisions are made directly on 1-3 millimetre plates (most commonly zinc, but copper is also used, as well as plexiglass) using a variety of fine steel chisels known as burins or gravers. As with all types of intaglio, the plate is prepared by sanding and polishing in order to clean away any imperfections which could collect residual ink and appear on the printed image.

The history of engraving can be traced back to the works of goldsmiths and silver engravers in 10th century China, as well as 13th century Europe. As a printmaking technique, engraving first appeared in the first decades of the 15th century, as a way of embellishing religious texts and books through illuminations. Nowadays, it is not so common among artists due to the slow process and the fact that one needs a lot of patience and a steady hand.

Engraving – Source: The Met Museum

Some of the most famous masters of 15th century engraving were the German artist Martin Schongauer (1435-1491) and the Italian goldsmith Tommaso Finiguerra (1426-1464). According to the writings of Giorgio Vasari, the artist that invented copperplate engraving was Andrea Mantegna. All three artists represented the art and printmaking of their time, with religious imagery, precision and intricate details. The end of the 15th century and first decades of the 16th were marked by the engravings of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).

According to some sources, Dürer learnt engraving at a very young age, producing his first known prints around 1497. Even though he saw the invention of etching and even created a small number of etchings around 1515, the artist went back to engraving, perhaps because it better reflected the relationship between the printed image and the movement of the body. While engraving depends solely on strength and precision, etching is a less direct printmaking process.

Etching

Etching is the most popular and most useful technique in printmaking, because it allows a lot of freedom for artistic expression. It is a chemical process, in which the matrix is created by submerging a metal plate into an acid or mordant. Depending on the type of metal (as with engraving, copper plates and zinc are most widespread), different acids are used, most commonly diluted nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and iron chloride.

Most of these acids are very aggressive and give off toxic fumes, with the exception of ferric chloride. Ferric chloride is a type of mordant based on corrosive salt crystals, and it has long been valued by printmakers for its safety and accuracy. The process of etching with ferric is very slow, but since the end of the 1990s, it has been perfected – the Edinburgh Etch, consisting of four parts ferric chloride solution and one part citric acid solution, works well on all types of metal plates and at greater speed. Innovations like the Edinburgh Etch are part of a growing concern for the environment among contemporary printmakers.

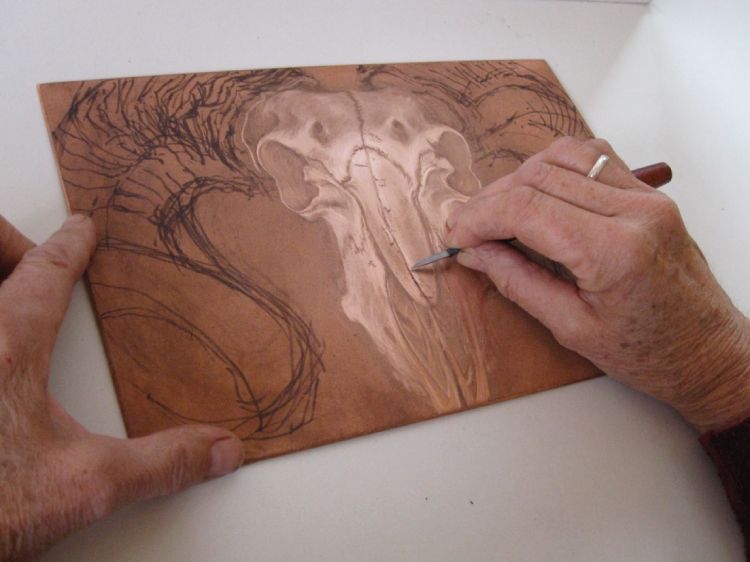

Etching Drawing into Ground on Copper Plate- Source: London Fine Art Studio

The plate is covered with an etching ground (tar, asphaltum, oil pastel, and sometimes even spray paint) to protect the surface from exposure to the acid, and parts of the ground are then removed to create a drawing. The back of the plate can be covered in brown tape to protect it from the acid. Different sizes and types of needles and tools can be used to create a sketch on the dried ground (You can use a sharp nail, a cheap option), exposing thinner and thicker layers to the acid.

Once the etching process is finished, the ground is removed with paint thinner or methylated spirits, and printmaking ink is applied onto the plate using the same principle of engraving. Depending on the strength of the acid and the length of exposure (etching) – the carved lines in the ground become lighter and darker lines on the print. If the plate is wiped thoroughly before printing, the print looks very much like an ink drawing. Intaglio prints can only be printed using a printmaking press, and the process requires higher quality 150-300g printmaking paper which can withstand being submerged in water.

Inked Etching Plate – Source: James McCallum

Note: Working with acids can be very dangerous. Please do not try any of these techniques before going through the necessary safety precautions. Acids can cause severe skin and lung damage. Never leave your plate unattended in a bath of acid, make sure to use glass and plastic containers to store acids, and never add water directly to an acid solution. It is strongly advised to get training at a printmaking workshop.

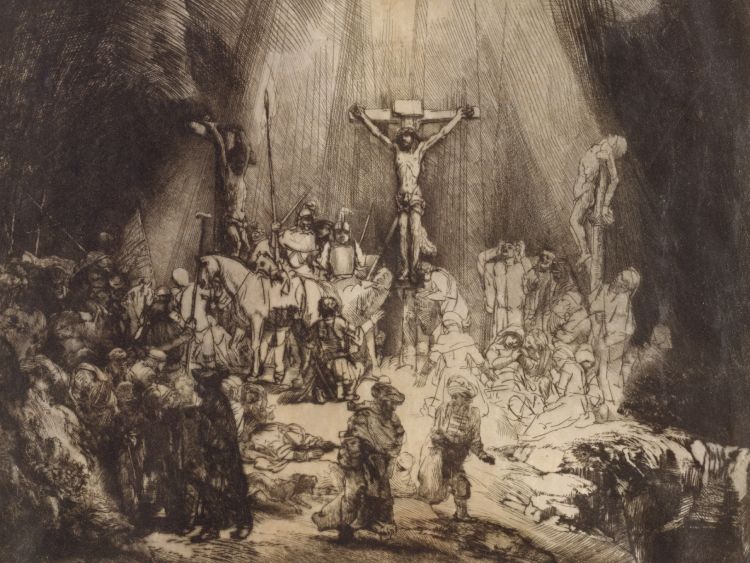

One of the most influential artists known for using and developing etching was Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). Working in the Netherlands in the 17th century, Rembrandt influenced many artists in the later decades, and contributed to a more nuanced approach to etching. Throughout his lifetime, he created more than 300 original etchings, including portraits and self-portraits, biblical illustrations, landscapes and nudes. Rembrandt’s works differed from the rigid traditional cross-hatching due to the freshness and playfulness of his lines and his use of residual ink to add subtle shading and atmosphere.

Rembrandt Windmill – Source: Met Museum

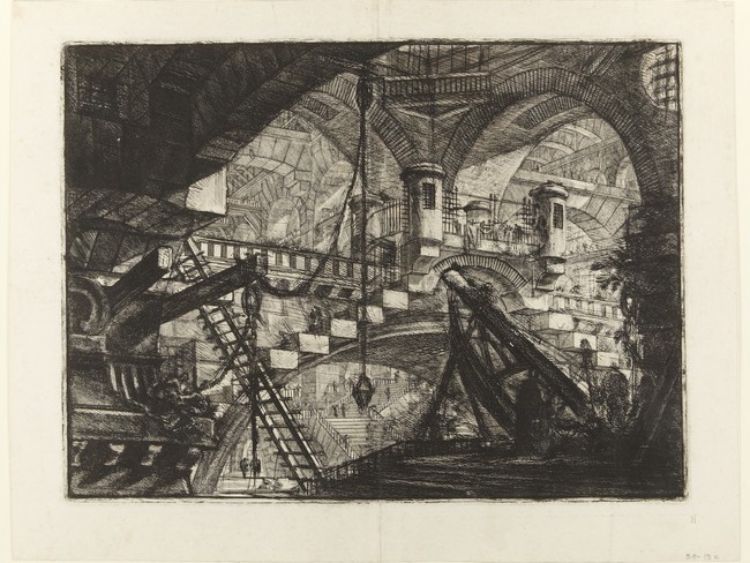

Several figures are worth mentioning when it comes to 18th century etching. The Italian architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) is best known for his depictions of Rome and the series of fictitious prisons known as Carceri. As one of the famous old masters of printmaking, the Spanish court painter and printmaker Francisco Goya (1746-1828) created several important series of etchings, including Los Caprichos, The Disasters of War, and Proverbs. Many of the works from these series had a strong political undertone, and they also included aquatint.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi – The Arch with a Shell Ornament- Source: Princeton University Art Museum

In the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, etching accompanied the artistic practice of many artists in different movements such as realism, romanticism, and impressionism. The French romantic painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) was known for his portraits, etched in minute detail and an impeccable sense of individual character. The impressionist painters Camille Pisarro (1830-1903) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917) also created a great number of etchings alongside their sketches and paintings, bringing a new sense of immediacy and movement to the technique.

Giorgio Morandi – Hilltop at Evening – Source: Tate

In the 20th century, when aesthetic pluralism was a priority, many artists enjoyed the versatility brought by etching. Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), the Italian artist known for his studies of light and shadow in austere still life, remains one of the printmakers most commonly associated with cross-hatching as a means of depicting values and contrast. On the other hand, an artist known for exploring many styles and techniques, also found his place among masters of etching.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) used etching throughout his career, but the most famous series he created in this technique is known as the Suite Vollard. Between 1930 and 1937, Picasso created 100 etchings for a commission made by the collector Ambroise Vollard (in return, Vollard offered Picasso paintings by Renoir and Cezanne!). Depicting scenes from an archetypal artist’s studio, nudes, portraits, myths and fantastic scenes, the series features exquisite linear drawing, hatched surfaces, and represent Picasso’s sense of composition and movement at their finest.

In terms of printmaking, the etchings are rather simple, with only a few different values of line and little to no shading. It is difficult to find this kind of simplicity in other examples of intaglio, as artists often opt for combining etching with aquatint for greater effect.

Aquatint

The aquatint process is younger than engraving and etching as it took artists more time to discover the right sequence of steps and recipes. The exact date and circumstances of the discovery are unclear, but no historical account of aquatint goes back further than the second half of the 18th century. Visually, the technique looks very similar to ink wash and it can be used to represent brushstrokes, although the differences in value between surfaces are sharper than in aquarelle and ink painting.

The process itself hasn’t changed much over the past two and a half centuries. In order to achieve balanced exposure to acids, the metal plate (prepared in the same way as with other techniques, making sure there is no grease on the surface) is covered by a thin layer of powdered rosin or colophonium. The powder is heated up at a high temperature until it melts, forming protective droplets that stick to the metal plate (matrix).

The same ground used for etching is applied onto the plate using a brush, covering the lightest parts of the original sketch first, and leaving the darkest shadows exposed the longest. Once the right depth is achieved, both the ground and the rosin are removed with paint thinner or spirits and alcohol respectively.

Short Process:

- The metal plate is dusted with a powdered resin and heated to make the resin particles adhere to the plate.

- The plate is then exposed to acid, which etches around these particles, creating a textured surface.

- Using various techniques, artists can block out or protect areas to control the depth of etch and resultant tone.

- Once etching is completed, the plate is inked and printed.

Effects: Aquatint is known for its broad tonal ranges, from the palest greys to deep blacks. It can create soft transitions or grainy textures, resembling the look of watercolour washes or sandpaper-like surfaces.

Aquatint is usually accompanied with other techniques, most commonly etching and drypoint, as the process can be difficult and often requires retouching. Many artists first create a light sketch on the plate using etching, and use drypoint to fix small mistakes or make surfaces darker when it’s needed. Two additional techniques that are not used as often as aquatint but have similar effects in terms of brushstroke are sugar lift etching and directly applying acid onto the plate with a brush (this is not a common practice because it is difficult to control the end results).

Otto Dix Shock Troops Advance After Gas – Source: Daily Art Magazine

One of the most prominent artists working with aquatint in its early stages was the French rococo painter and printmaker Jean Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781). Most notable for depicting decorative landscapes and court scenes, Le Prince was a master of aquatint known for working with several plates of different colours. However, the most unique works of aquatint can again be found in the series Caprichos and The Disasters of War by Goya.

Goya combined aquatint with subtle sketches in etching and drypoint, but the atmosphere of movement and the interplay of lightness and shadow would not have been so successful without his mastery of aquatint. Edouard Manet (1832-1883), the pioneer of French impressionism, was also known for accompanying his painterly practice with etching and aquatint. From 20th century artists, the anti-war prints of Otto Dix (1891-1969) and the various intaglio experiments of Picasso provide great examples of the possibilities of aquatint.

Drypoint

Drypoint is a popular type of intaglio printmaking because it’s a non-toxic, mechanical method, less complicated than etching and less physically demanding than engraving. It is often used in addition to other techniques as it is perfect for initial sketching on the plate, or fixing small mistakes on an etched matrix.

The matrix is usually a copper or zinc plate (although new materials like plexiglass are nowadays becoming increasingly popular) and lines are scratched directly onto it with a steel needle making it much closer to drawing than any other technique. While it is great for making fresh sketches, drypoint is not very useful for creating a large number of impressions because the needle doesn’t scratch far beneath the surface of the plate.

Rembrandt – Christ Crucified – Source: Met Museum

Dürer created only four drypoint prints between 1510 and 1515, but Rembrandt was known for using drypoint more than any other artist of his time. Under Rembrandt’s influence, a number of 18th century English printmakers became interested in drypoint, including Thomas Worlidge (1700-1766), Benjamin Wilson (1721-1788), and Richard Byron (1724-1811). The full expressive potential of drypoint wasn’t discovered until the 20th century and the rise of expressionist art. Many notable 20th century artists created exquisite drypoint prints, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Otto Dix, Pablo Picasso, Max Beckmann (1884-1950), and others.

Mezzotint

Mezzotint, or ‘the dark manner’ is another mechanical printmaking technique from the intaglio family which depends mostly on the artist’s patience. Unlike other techniques, the process of preparing a plate for mezzotint is different and doesn’t involve sanding and polishing the metal surface but the complete opposite. A medium-dark tone is created as a starting point for printing with a special tool called a rocker – the rocker is used to create indentations in the plate which will hold ink and print as a dark surface.

Rocking the plate can take a lot of time as it needs to be done several times on each side to ensure a balanced tone (In my studies it was on a circle with 40 rotations, it took a very long time). Once the plate is rough enough, a sketch is transferred and polishing tools/dental tools are used to even out the parts that are supposed to be lighter. In order to achieve the right contrast, usually we make many test prints throughout the process. Many artists find mezzotint to be too time-consuming, but others enjoy the fact that the end results depend solely on their own work (whereas chemical processes like etching and aquatint often come with surprises).

Short Process:

- The entire plate is roughened using a tool called a ‘rocker’ resulting in a textured surface that, when inked, would produce a completely dark print.

- Using various burnishing tools, the artist smoothens areas of the plate to create lighter shades.

- The plate is inked and then printed, capturing the tones created by the varied surface textures.

Effects: Mezzotint is renowned for its rich, velvety darks and detailed highlights. It’s ideal for capturing dramatic light effects, like the soft glow of candlelight or the depth of a nocturnal scene.

Mezzotint Working Plate – Source: The Drawing Studio

The discovery of mezzotint is attributed to the German soldier and amateur engraver Ludwig von Siegen (1609-1680). Von Siegen’s first known mezzotint was a portrait from 1642, very typical for 17th century art yet exquisite in terms of the fine details and subtle play of light. Mezzotint quickly gained popularity in the 17th century, and artists like Wallerant Vaillant (1623-1677), William Sherwin (1669-1714), and Ruprecht von der Pfalz (1619-1652) created several hundred prints during their careers.

English printmakers of the 18th and early 19th centuries like William Ward (1762-1826) and James Ward (1769-1859), George Dawe (1798-1829), and Charles Turner (1774-1857) created many impressive portraits in mezzotint, although many of them used the paintings of great masters for reference. The fact that the process of preparing a plate for mezzotint takes so much time and effort makes this technique slightly less popular among artists.

Stippling

Stippling is an intricate etching technique that involves the meticulous application of tiny dots onto a prepared metal plate using a special etching needle. This dot-based method is akin to pointillism in painting, where the overall image emerges from these individual points. When the plate is immersed in an acid bath, the acid interacts with the exposed areas, creating varying tones based on the density of the dots. The end result is a print with soft tonal gradations, allowing for subtle transitions and an almost photographic quality. This method is perfect for artists aiming to achieve detailed, realistic imagery.

Short Process:

- Prepare the metal plate by cleaning and ensuring its free of scratches, coat with chosen ground.

- Using a special etching needle, create a series of dots onto the plate’s surface.

- The plate is then immersed in an acid bath, which eats away at the exposed areas.

- The plate is inked, wiped clean, and pressed onto paper to produce the print.

Effects: Stippling creates a delicate tonal gradation based on the density of the dots. The closer and more frequent the dots, the darker the shade produced. It allows for soft transitions, making it perfect for detailed, realistic images.

Spit Bite

A technique that aligns closely with the spontaneity of painting, spit bite offers artists a direct and expressive approach to etching. By applying acid directly onto the metal plate using brushes or other tools, artists can achieve an array of organic marks and tones. The length of time the acid remains on the plate determines the depth and intensity of the etch, giving creators precise control over the results. Prints produced using the spit bite technique often resemble watercolour paintings, boasting wash-like tones, fluid transitions, and a unique, unrestrained quality.

Short Process:

- Paint acid directly onto the metal plate using a brush or other applicator.

- The duration the acid remains on the plate controls the depth and darkness of the mark.

- Once desired etching is achieved, the plate is rinsed.

- Ink the plate and print as with other etching techniques.

Effects: Spit bite offers a more painterly and organic effect. The technique gives artists more direct control, allowing for spontaneous marks, wash-like tones, and varied textures. It can produce results similar to watercolour paintings.

Conclusion

Unlike woodcut, linocut and screen printing, the different types of intaglio printmaking take a bit more effort and time due to their use of chemicals and professional tools. Even though it can require special skills and is usually a bit pricier than other printmaking techniques, intaglio has played an important part in the development of fine arts, and it still offers a lot of space for experimentation for artists today. The fact that it requires a lot of attention and direct handling often presents an opportunity to distance oneself from the digital realm and go back to the physicality of the artistic process. Additionally, many artists nowadays are looking into new materials which could make the process less toxic and more environmentally sustainable.

If you would like to try out one or more of these techniques, please feel free to look into the additional resource list provided below and make sure you check the necessary safety precautions before you start.

Additional Resources

- https://handprinted.co.uk/blogs/blog/drypoint-printing

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SNKn4PORGBI&ab_channel=MinneapolisInstituteofArt

- http://wsa.wikidot.com/intaglio-resources

- https://www.cansonstudio.com/creating-various-shades-colour-using-aquatint-technique

- https://blog.artweb.com/how-to/aquatint/

- https://risd.libguides.com/c.php?g=866191&p=6538250

- https://seacourt-ni.org.uk/intaglio-printmaking-resource/

- https://www.dorsetfinearts.com/etching-and-aquatint

- https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/printmaking/etching

- https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/aquatint-print-technique

- https://magical-secrets.com/studio/better-sugar-lift/

- http://www.leicesterprintworkshop.com/files/uploads/sugar_lift_etching.pdf

- https://www.artelino.com/articles/intaglio_printmaking.asp

- https://artinprint.org/article/freedom-and-resistance-in-the-act-of-engraving-or-why-durer-gave-up-on-etching/

- https://magical-secrets.com/process/

- https://www.greenart.info/galvetch/etchtabl.htm

- https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/94303

- https://www.simondickinson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Morandi-Linear-Impulse-brochure-final-email.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jan/13/morandi-lines-poetry-review-giorgio

- https://www.simondickinson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Morandi-Linear-Impulse-brochure-final-email.pdf

- https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-2374.html

- https://www.parkwestgallery.com/francisco-goya-disasters-of-war/

- https://archive.org/details/printsprintmakin00grif/page/39/mode/2up

- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mztn/hd_mztn.htm

- https://clarklibrary.ucla.edu/blog/seventeenth-century-printmaking-mezzotint/

Why do you think intaglio printing was so commonly used, despite its difficulty?

FAQ: Intaglio Printing

Question: Why do you think intaglio printing was so commonly used, despite its difficulty?

Answer: Intaglio printing was widely adopted because of its unparalleled ability to produce fine, detailed lines and rich textures, which were highly valued in artistic and commercial printmaking. Despite the laborious and technically demanding process, artists and printers favoured intaglio for its versatility and the quality of its output. The process allowed for a wide range of tonal variations and intricate details that were difficult to achieve with other printing methods. Additionally, intaglio prints were highly durable and could be reproduced multiple times without significant degradation of image quality, making it a practical choice for both art and industry.

How is a mezzotint piece created? Why is it unique and important to intaglio printmaking?

FAQ: Mezzotint Printmaking

Question: How is a mezzotint piece created? Why is it unique and important to intaglio printmaking?

Answer: A mezzotint piece is created by first roughening a metal plate uniformly with a tool called a “rocker,” which creates a textured surface that can hold ink. The artist then works the plate by scraping and burnishing areas to smooth out parts of the texture, creating gradients from dark to light. This results in a print with rich, velvety blacks and a wide range of tonal values, often giving the finished piece a highly detailed and realistic appearance. Mezzotint is unique because it allows for the creation of subtle gradations of tone, making it particularly effective for rendering shadows and depth. This method was significant in intaglio printmaking as it enabled artists to achieve photographic levels of detail and richness in their prints, contributing to the evolution of print as a respected art form.

Which of the following forms of intaglio are most similar to drawing?

FAQ: Intaglio Printmaking Techniques

Question: Which of the following forms of intaglio are most similar to drawing?

Answer: Of the various forms of intaglio printmaking, etching is the most similar to drawing. In etching, an artist uses a needle to draw directly onto a metal plate that has been coated with an acid-resistant ground. The exposed metal lines are then etched or bitten into the plate by immersion in acid, creating grooves that hold ink. This technique closely mimics the process of drawing with a pen or pencil, allowing artists to create intricate and expressive lines with varying pressure and spontaneity. The directness and immediacy of the etching process make it particularly appealing to artists who are skilled in drawing.