“All art is political.”

This oft-repeated phrase, of a somewhat elusive origin, reflects a profound truth about creative expression: art is a powerful medium—capable of stirring emotions, shaping perceptions, and communicating complex ideas without a single word—, and, as the product of a human mind, it inevitably carries fragments of the artist’s world, beliefs, and surroundings. Even the seemingly frivolous, even when its intentions appear far removed from governance or ideology, it inevitably reflects the times and values in which it was created.

Throughout history, art has often served as a weapon of protest, a voice for the silenced. Protest songs of the 1960s gave rhythm to movements for civil rights and peace, while visual masterpieces like Goya’s The Third of May 1808 and Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People captured the raw defiance of resistance against tyranny. But while rebels and revolutionaries have wielded it as a tool of dissent, so too have governments harnessed it to exert control over their people.

From monumental architecture to propagandistic films, from meticulously designed uniforms to symbolic colour palettes, authoritarian regimes have long understood the ability of visual culture to cement their ideologies and command the masses. This is the story of how dictatorships weaponised aesthetics—not merely to reflect power but to define it, manipulate it, and make it inescapable.

Table of Contents

Key Approaches to Art and Design in Dictatorships:

Monumental Architecture

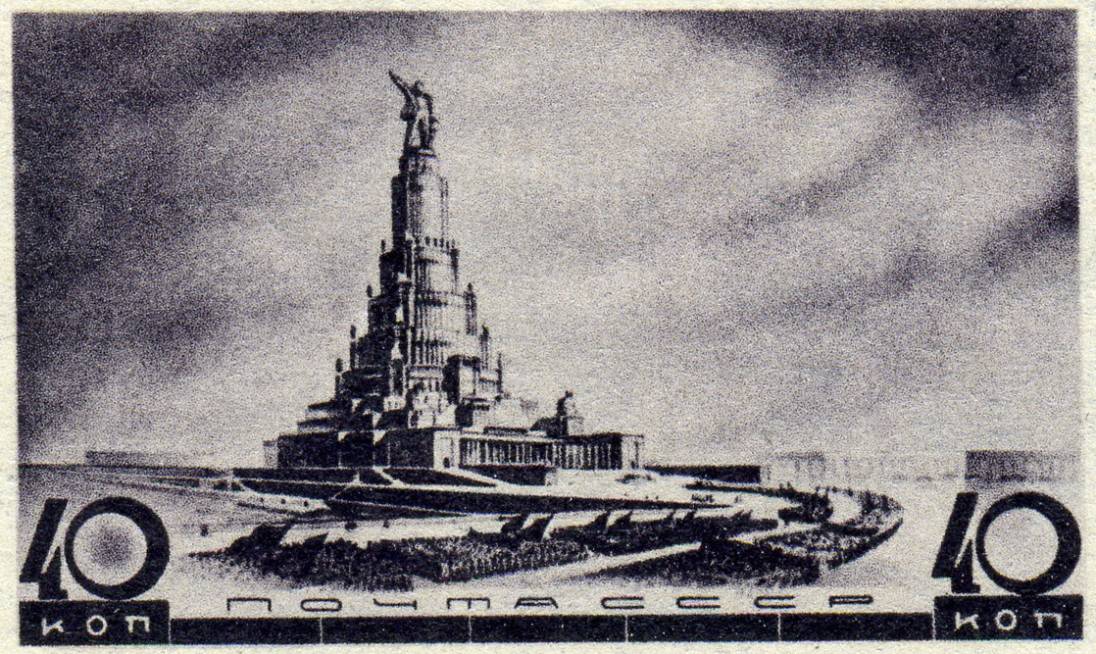

The Soviet Union 1937 CPA 551 sheet of 4 (4 x Palace of the Soviets) – Source: Wikipedia

“The Ministry of Truth contained, it was said, three thousand rooms above ground level, and corresponding ramifications below. Scattered about London, there were just three other buildings of similar appearance and size. So completely did they dwarf the surrounding architecture that from the roof of Victory Mansions you could see all four of them simultaneously. They were enormous pyramidal structures of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air.” George Orwell, 1984.

Totalitarian regimes have always understood the symbolic power of architecture. More than just shelter or infrastructure, buildings under authoritarian rule often serve as physical manifestations of ideology, where large-scale, imposing structures are designed to project power, permanence, and control over both the landscape and the people who inhabit it.

These architectural projects, that receive the name of totalitarian architecture, often fall into two categories. On one hand, functional and austere designs for residential blocks or government offices conveyed an unadorned efficiency—spaces devoid of individuality, often built to allow for surveillance and to emphasise the collective over the personal. Often akin to giant prisons, these structures reinforced the regime’s watchful presence and the erasure of dissent.

On the other hand, monumental buildings—palaces, grand halls, and memorials— glorify the state. Opulent and grandiose, monumental architecture intended to overshadow past regimes and dazzle both citizens and adversaries. Stalin’s proposed Palace of the Soviets, for instance, was envisioned as a towering symbol of Soviet superiority, outshining the architectural achievements of the tsars. The project, although never completed, embodied the narrative of modernisation and progress that Soviet propaganda sought to instill.

In this sense, beyond its pragmatic nature, architecture also plays a role in propaganda art, as a storytelling tool utilised to explore ideas of supremacy, excellence, unity, and eternity pushed by totalitarian governments. Saddam Hussein’s Iraq utilised grand structures to link his rule to ancient Mesopotamian empires, fabricating a narrative of historical continuity and cultural dominance. Similarly, the Nazi regime, under Albert Speer’s direction, designed structures intended to last for a thousand years, embodying the myth of the eternal Reich.

The Kumsusan Palace of the Sun stands as a mausoleum and symbol of unity, blending modernism with traditional Korean motifs to exalt the Kim dynasty whilst emphasising the idea of continuity and stability, whilst in Spain the Valley of the Fallen (which could be seen as an intent to reproduce the Egyptian Valley of the Kings) combines religious and nationalist themes, imposing a vision of eternal authority over the landscape.

Poster Art and Propaganda Imagery

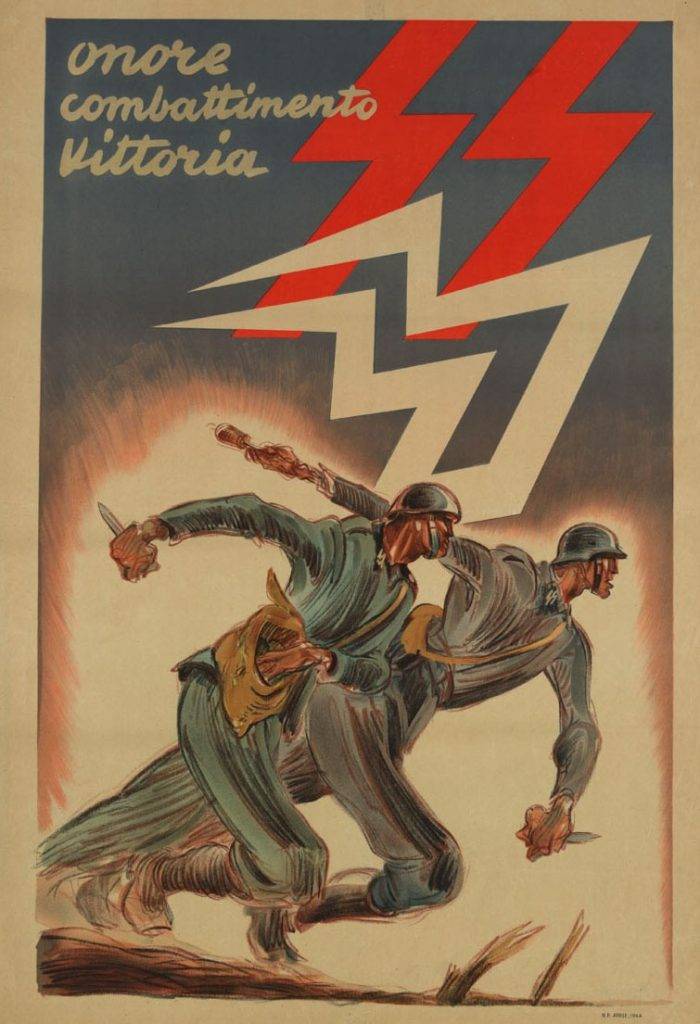

Onore Combattimento Vittoria (1944) – Source: Weirditaly.com

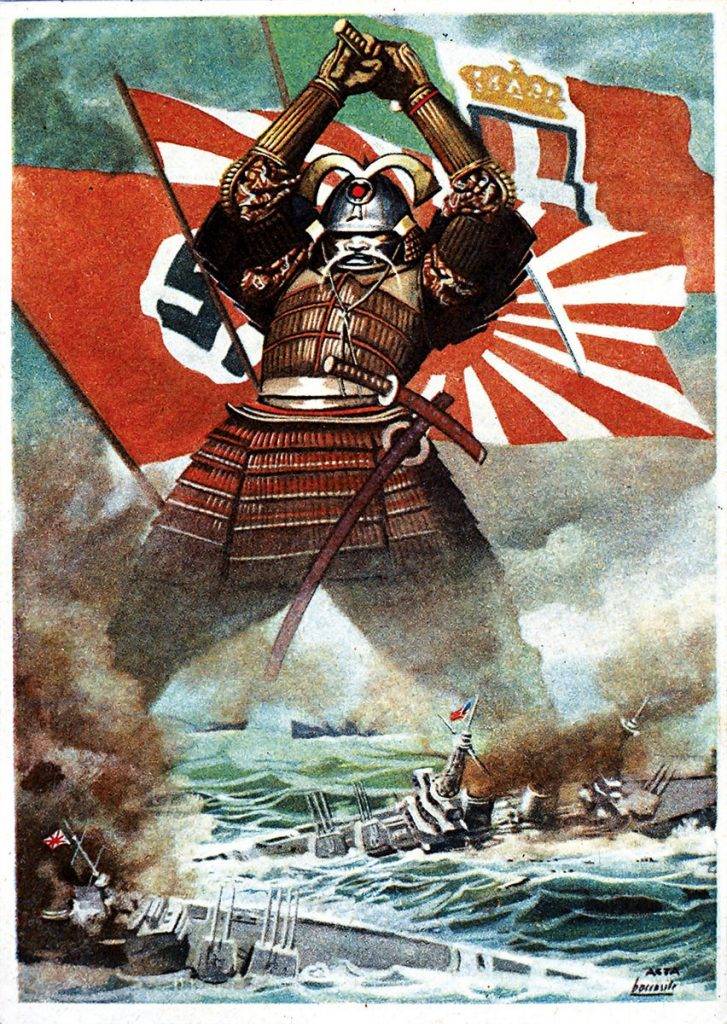

In the hands of authoritarian regimes, propaganda art became a powerful tool to glorify leaders, reinforce ideologies, and inspire collective action. While monumental architecture was designed to dominate the skyline and instil awe, poster art spoke directly to the people, urging them to participate in the regime’s grand narrative. Whether calling young men to war, encouraging families to buy national products, or warning citizens to remain vigilant against enemies, these posters were less about projecting oppression and more about fostering empowerment and unity—at least on the surface.

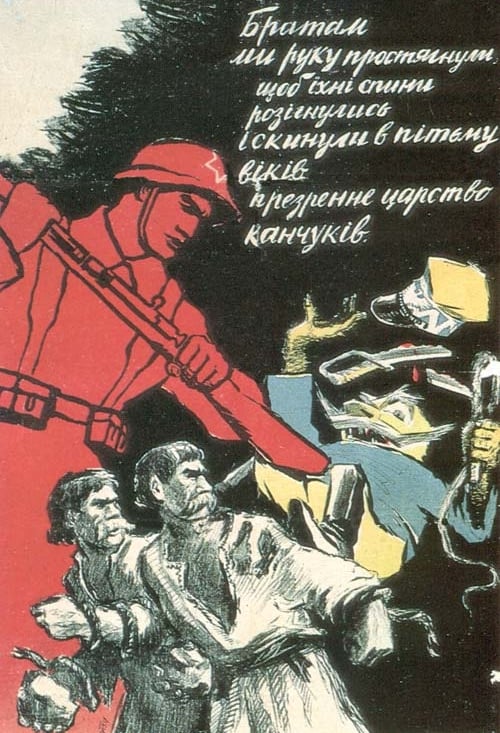

A hallmark of Soviet propaganda, for example, was its depiction of workers and soldiers as heroic figures. In Socialist Realism posters, muscular men operated machinery with determined expressions, while women—often dressed in agricultural or industrial uniforms—smiled radiantly as they worked, embodying the regime’s vision of a utopian, classless society, supported by the tireless efforts of the proletariat. Meanwhile, the backdrop of factories or collective farms reinforced the narrative of progress and modernisation central to Stalin’s vision.

In contrast, the enemy in such imagery was portrayed in negative terms. The “other” was often dehumanised—grotesque, menacing, and cruel. This tactic was particularly evident in military aesthetics employed by Imperial Japan, where posters depicted Allied soldiers as savage threats while idealising Japanese soldiers as noble warriors or protectors of the nation. These visuals, often enhanced with national symbols like cherry blossoms or samurai motifs, evoked pride and justified the sacrifices demanded by the regime.

The use of modern art movements also played a crucial role in the design of these posters. Borrowing elements from futurism and constructivism, the bold lines, geometric shapes, and striking colour palettes gave the art a dynamic quality that demanded attention. In Fascist Italy, these aesthetics were combined with an emphasis on Mussolini himself, who was frequently depicted as a larger-than-life figure—a symbol of unyielding strength and national revival.

The Cultural Revolution: all you need to know about China’s political convulsion – The Guardian

Similar themes appeared in Maoist China during the Cultural Revolution. Vivid posters, dominated by the colour red, depicted soldiers, farmers, and factory workers marching in unison beneath images of Mao Zedong. These carefully crafted pieces of propaganda art highlighted unity and loyalty to the Communist Party, portraying Mao as both a benevolent leader and a god-like figure. The art celebrated the collective struggle while urging citizens to dedicate themselves to the revolutionary cause.

Even outside the Communist and Fascist spheres, other authoritarian regimes harnessed the power of visual culture. Argentina’s military regime used posters to depict the state as a bastion of stability, emphasising discipline and security while instilling fear of subversion.

Across these examples, one constant remains: authoritarian regimes and visual culture are inseparable. Propaganda imagery functioned not only as a means of communication but also as a way of shaping public consciousness, rallying support for the regime’s goals while vilifying its opponents. Poster art, whether inspiring hope or fear, was instrumental in crafting a sense of identity and unity under the regime’s control.

Film and Visual Media

Under authoritarian regimes, film and visual media served as one of the most potent instruments of propaganda art, wielding the power to shape narratives, promote state ideologies, and cement loyalty to the regime. Dictatorships not only leveraged media to celebrate nationalist values but also imposed strict censorship, erasing dissenting voices and ensuring that only state-approved messages reached the masses.

Nazi Germany provides a stark example of how cinema was used to reinforce political symbolism and shape public perception. As Joseph Goebbels made clear in a speech in 1933, he had a vision for German art under National Socialism, including cinema, as “heroic, steely but romantic… nationalistic with great depth of feeling; it will be binding, and it will unite, or it will cease to exist” (Peter Longerich, Goebbels: A Biography). However, heavily politicised movies often failed to resonate with the public. A 1935 report by the underground German Social Democratic Party noted: “The movie theatres are rather well attended. Foreign films and harmless entertainment films are the best visited. Nazi films, like Triumph of the Will, are being avoided.” This lukewarm reception prompted the regime to adapt its approach, embedding subtler ideological messages into entertainment films that were more palatable to audiences.

In the Soviet Union, cinema played an equally central role in the regime’s agenda. Films like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin became iconic for their revolutionary themes and emotional impact. Through its dramatic portrayal of a mutiny against oppressive forces, the film epitomised Soviet propaganda by aligning its narrative with communist ideals of collective struggle and defiance against tyranny. Meanwhile, Soviet animation of the 1940s and 1950s targeted younger audiences, adapting Russian folklore and literary works into a Disney-inspired naturalistic style. As Anatoliy Klots explains, this era of animation “was aimed at children to promote loyalty to the country, a positive attitude towards Socialist society, and the common values of friendship, honesty, and politeness.”

Across authoritarian regimes and visual culture, propaganda films worked to merge ideology with entertainment. In Imperial Japan, cinematic works glorified traditional values like honour, discipline, and loyalty to the Emperor, reinforcing these ideals through heroic war narratives. Similarly, North Korea’s film industry continues to craft elaborate stories in which the Kim family are portrayed as almost mythical figures, saviours who protect the nation against external threats.

Spain under Franco provides another fascinating example of how film reinforced control. Before any movie screening, cinemas were required to show the Noticiarios y Documentales (No-Do), a state-mandated newsreel brimming with nationalist propaganda. This ritual embedded state narratives into the everyday lives of citizens, normalising the regime’s values. Having grown up in Spain in the 1990s, I of course never witnessed a No-Do newsreel live, but my parents’ generation still recall them vividly, often more as an object of mockery (that has been ridiculed in satiric TV shows ever since they were discontinued in cinemas) than as a pervasive instrument of propaganda filmography.

Symbolism, Colours, and Iconography:

Kremlin Red Star – Source: Wikimedia Commons

Through their calculated use of political symbolism, authoritarian regimes crafted a powerful, often chilling, visual identity that permeated daily life. By intertwining militaristic imagery with cultural and historical references, they sought not only to control but also to inspire, manipulate, and unify their populations under the banners of ideologies that promised—and demanded—absolute allegiance.

The political symbolism of dictatorships, however, isn’t one that suddenly appears out of thin air. Many of the symbols that we identify and link to these ideologies predated them, and were deliberately chosen, often adapted from ancient imagery to evoke a sense of continuity with a “glorious” past. It is not ironic, but rather strategic, that these parties adapted this and other symbols from civilisations with which they shared no other similarities, as they already resonated with cultural and historical significance, making them effective tools to promote a revolutionary agenda while embedding themselves in the nation’s collective consciousness.

The Nazi swastika, for instance, is an ancient symbol of prosperity and well-being found across cultures, from Hinduism to Native American traditions. The Nazis transformed it, rotating it and embedding it in a stark black-and-red colour scheme. Similarly, the eagle—another Nazi symbol—harkened back to the Roman Empire, a deliberate attempt to position the Third Reich as the successor to an imperial legacy of strength and expansion.

Similarly, the red star, now synonymous with communism, has roots in Tsarist Russia, where it was referred to as the “Mars star,” a nod to Mars, the Roman god of war. Its transformation into a political symbol highlights how authoritarian regimes and visual culture often co-opted existing imagery to construct new meanings that supported their ideologies. On the other hand, the hammer and sickle, one of the most recognisable symbols of Soviet propaganda, also predates the communist regime, originally associated with the tools of labourers and peasants, adopted to represent unity between the working class and the peasantry.

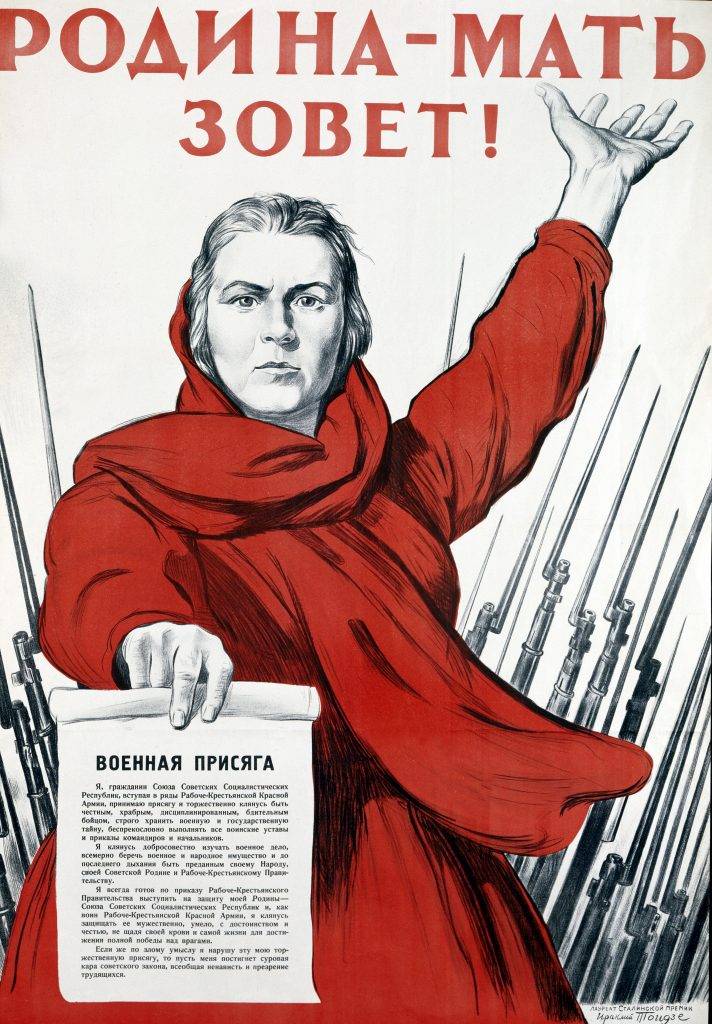

Iconography could also extend to personifications of the state. In Soviet Russia, the image of “Mother Russia” became a central figure, embodying the homeland’s endurance and nurturing qualities, appearing in propaganda posters and literature, such as Maxim Gorky’s Mother. It reached its zenith during World War II, symbolising the collective effort to defend the Soviet Union.

“Motherland is calling” by Irakly Toidze (1941) – Source: PBS News

Clothing Design and Uniforms

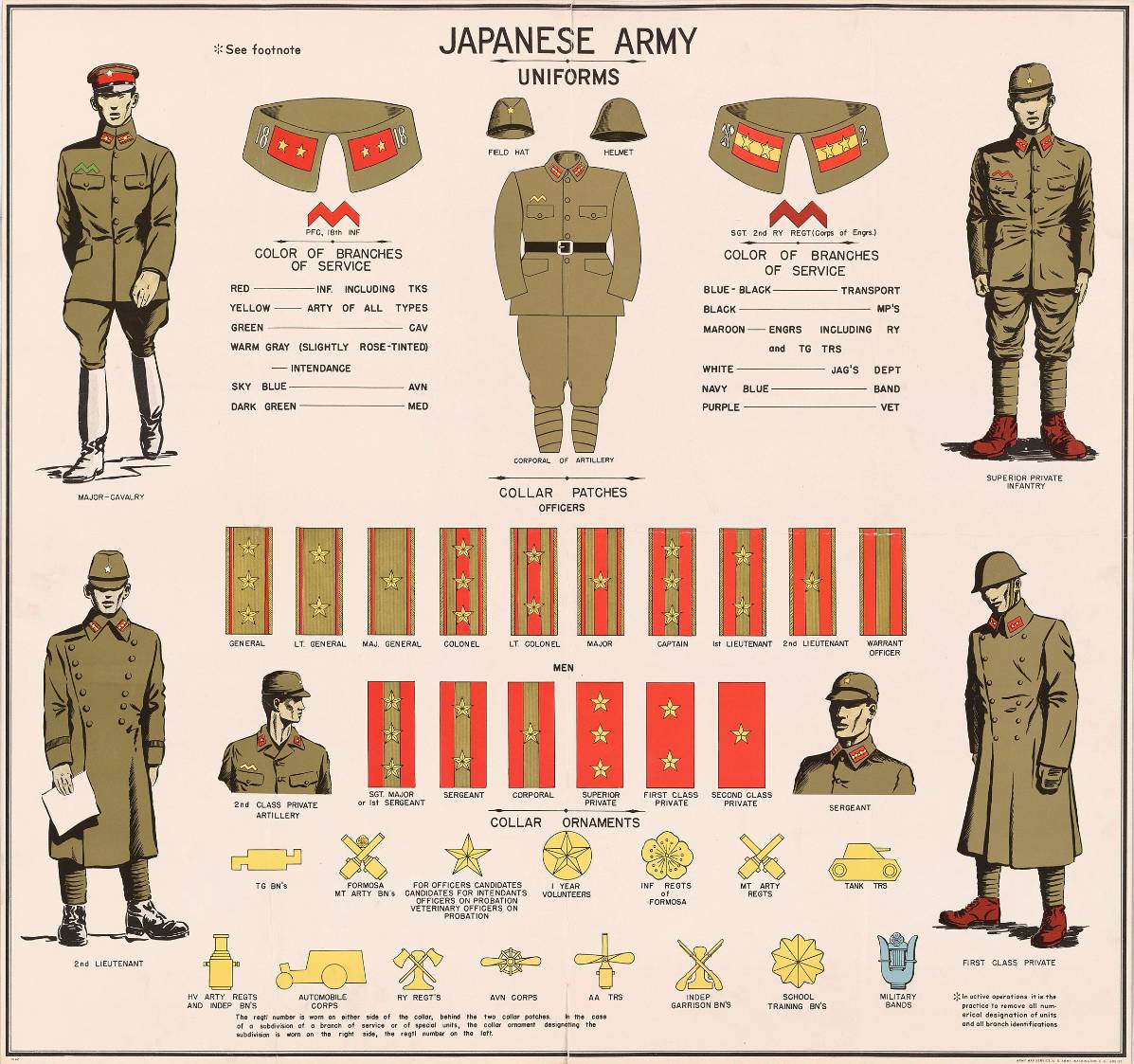

WW2 Japanese Army Uniforms Rank – Poster chart (1944) – Source: Wikimedia Commons

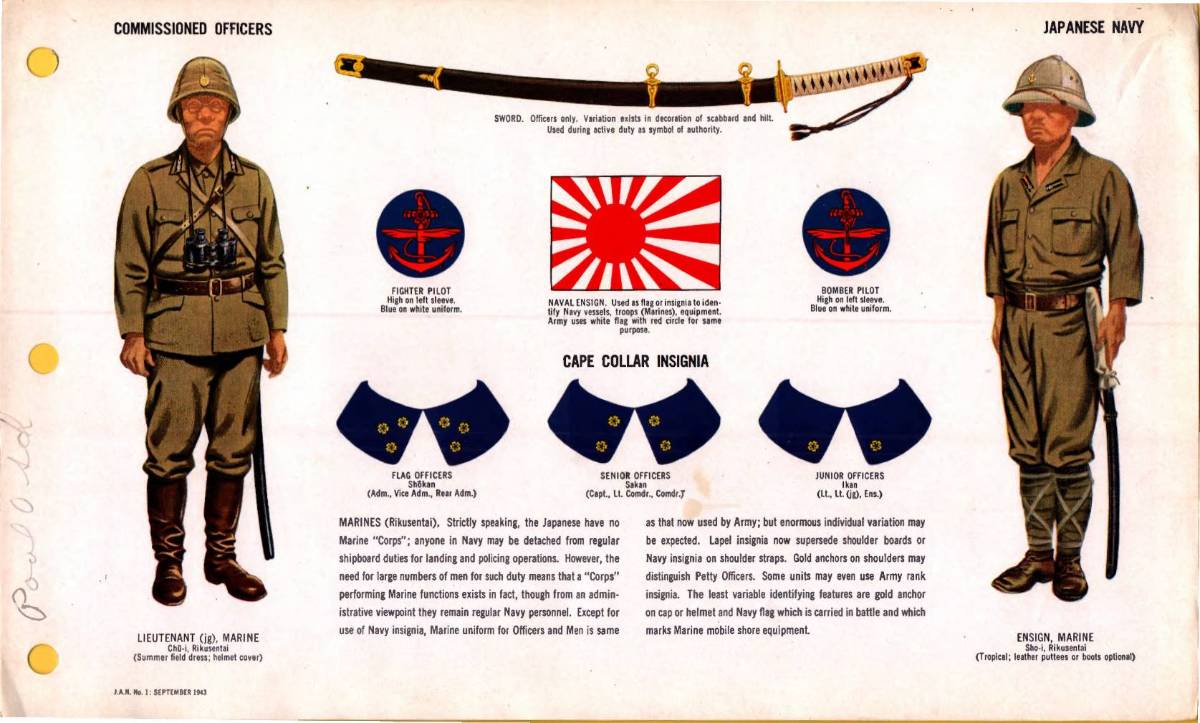

Dictatorships carefully crafted their uniforms to be more than mere attire; blending military aesthetics with visual messaging, they were wearable propaganda, reinforcing the power of the state and the submissiveness of the individual to it.

The Nazis are a prime example of this calculated use of uniform design. Their uniforms, particularly those of the SS, were designed with stark precision. Black dominated the colour palette, evoking authority, formality, and menace, while red and white insignias added contrast, drawing attention to Nazi symbols such as the swastika. The skull-and-crossbones insignia on SS caps, an ancient symbol of mortality, was co-opted to strike fear into both enemies and citizens, embodying the lethal power of the organisation. These uniforms, designed by Hugo Boss, reflected a chilling marriage of aesthetics and intimidation, enforcing the regimented image of the Nazi regime.

In Fascist Italy, uniforms took on a similarly militaristic style, with dark colours symbolising strength and unity. Black shirts, famously worn by Mussolini’s paramilitary squads, became iconic, creating a clear visual identity for the Fascist movement. Their simplicity and starkness contrasted with the decadence associated with Italy’s pre-Fascist era, marking a shift to a more disciplined, martial society.

In Maoist China and North Korea, uniforms were central to fostering a collective identity. The ubiquitous khaki and military-style outfits of the Cultural Revolution served to erase individual differences, aligning everyone with the revolutionary cause. The muted colours symbolised egalitarianism and the rejection of bourgeois decadence. In North Korea, similar uniforms became a visual representation of the merging of civilian life and military order.

Similarly, during Argentina’s military dictatorship (1976–1983), the junta’s military attire, often in shades of olive green and khaki, emphasised authority and control while downplaying ostentation. The insignias, medals, and rank markings on these uniforms conveyed hierarchy and discipline, ensuring every interaction with the public became a reminder of the state’s dominance.

In contrast, Japan’s WWII military uniforms took a slightly different approach, drawing on traditional values and historical symbolism. The design emphasised cultural pride, using features like the imperial chrysanthemum insignia and red accents to evoke a sense of divine mission and national unity. The uniforms’ aesthetic bridged the past and present, reinforcing the idea of Japan as a nation with an unbroken and noble lineage.

Uniforms and Insignia Page 072 Japanese Navy WW2 Commissioned officers (1943) – Source: Wikimedia Commons

The deliberate choice of colours, insignia, and styles across these regimes mirrored the broader strategies seen in political symbolism and propaganda. Red, black, and white, for instance, were commonly used to project power and solidarity, while military cuts and designs blurred the boundaries between civilian and soldier, creating a sense of perpetual readiness for war or sacrifice. In every instance, uniforms weren’t just clothing—they were an extension of the state’s ideology, turning wearers into living representations of its values

Control over Fine Arts

Roses for Stalin, by Boris Vladimirski (1949) – Source: Artmejo.com

Dictatorships, regardless of ideology, have consistently demonstrated an aversion to abstract art. And the reason might be simple: abstraction invites interpretation. A painting that might symbolise rebellion against capitalism to one viewer could suggest defiance of communism to another—or it might mean nothing at all. For art to serve a regime’s agenda, its message must be unequivocal, unavoidable, and entirely aligned with state ideology. There can be no ambiguity; the meaning has to be prescribed and absolute, leaving no room for alternative narratives.

This insistence on clarity naturally gravitated totalitarian regimes towards realism, particularly a heroic, idealised form of realism that centred on strong, muscular figures. While the stylistic outcome appeared similar across regimes, the motivations diverged.

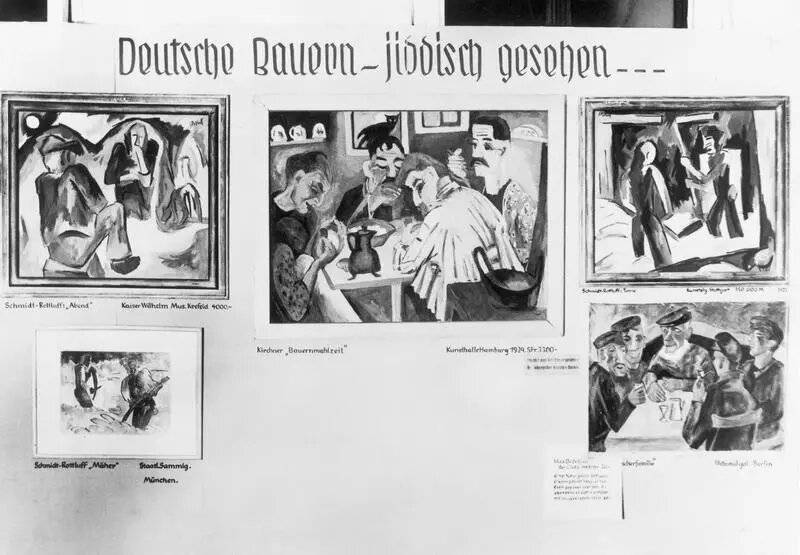

In Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler’s disdain for modern art was rooted in racist ideology. According to historian Henry Grosshans in Hitler and the Artists, Hitler perceived Greek and Roman art as pure and “uncontaminated by Jewish influences.” By contrast, he viewed modern art as “an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit.” This led to the classification of modernist works as Entartete Kunst—degenerate art. Even though only a small number of prominent modernist artists were Jewish, Hitler used this association to demonise the movement. A notorious 1937 exhibition of degenerate art in Munich displayed works by renowned artists like Kandinsky, Chagall, and Picasso, mocking them as evidence of cultural decline. In contrast, under Nazi control, fine art glorified the Aryan ideal: heroic, athletic men, serene women, and idyllic rural landscapes, all embodying the regime’s vision of racial purity and national strength.

In the Soviet Union, Socialist Realism emerged as a tool to construct the “New Soviet Man.” Anatoly Lunacharsky, head of the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment (Narkompros) in the early Soviet era, developed an aesthetic philosophy centred on the human body. He believed that “the sight of a healthy body, intelligent face or friendly smile was essentially life-enhancing.” This philosophy (although not officially adopted until adopted) as noted by art historian Andrew Ellis in Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970, held that by depicting idealised, flawless citizens, art could educate the masses on how to embody the perfect Soviet ideal. Socialist Realist works often featured factory workers, farmers, and soldiers, portrayed with unwavering confidence and strength, reinforcing the state’s promise of a utopian socialist future. Avant-garde movements, which had thrived during the early Soviet years, were systematically suppressed as being “bourgeois” or “formalist,” a rejection of the innovation and abstraction these styles embraced.

Kolkhosians lets exercise by Alexandre Deineka – Source: PBS News

Fascist Italy’s approach to art was notably more flexible compared to the rigid cultural controls of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. While Mussolini’s regime promoted a range of styles, from neoclassicism to modernist movements like Novecento Italiano, it also embraced avant-garde groups like the Futurists, who aligned with the state’s vision of progress and dynamism. Unlike the Nazis’ outright rejection of modernism or the Soviets’ strict adherence to Socialist Realism, Mussolini tolerated a plurality of artistic expressions, provided they didn’t openly criticise Fascism. This pragmatism reflected the regime’s broader strategy to associate itself with both the grandeur of ancient Rome and the innovation of the modern age. Although dissent was still suppressed, Italian artists often enjoyed greater freedom to experiment, contributing to a uniquely diverse artistic landscape under authoritarian rule.

Similarly, the relationship between dictatorship and art in Spain under Franco was somewhat different compared to other totalitarian regimes. While Franco’s government heavily censored literature, film, and other media, visual art didn’t seem to face the same level of ideological imposition. Artists who stayed in Spain during the dictatorship often navigated this “exilio interior” by creating work that avoided overt political commentary. Franco’s regime preferred to focus on promoting conservative and religious iconography aligned with Catholic values and Spanish nationalism. Unlike Soviet Socialist Realism or Nazi condemnations of “degenerate art,” there wasn’t a unified or explicitly mandated artistic style under Franco. This absence of strict directives allowed certain forms of abstract or non-confrontational art to persist, though always under the shadow of potential censorship. Artists like Antoni Tàpies, for instance, emerged during the later years of Franco’s rule, blending abstract and surrealist styles that avoided direct political statements while still resonating with themes of human struggle and resilience.

Impact and Legacy

The aesthetic legacies of authoritarian regimes serve as a striking reminder of how deeply art and design can shape political landscapes. From the monumental architecture of Nazi Germany to the propaganda art of the Soviet Union, the deliberate use of political symbolism and visual culture not only unified populations but also left an enduring imprint on history. Today, these artistic choices provoke discourse, reminding us of the power wielded by dictatorships through creative mediums. They underscore how profoundly design—whether through fashion, architecture, or visual art—can be weaponised to control narratives and perpetuate ideologies, leaving a complex and often haunting cultural legacy.