Article commissioned by Hickman Design, Author – Dunja Karanovic

In a sense, the practice of printmaking is as old as visual culture itself. Consider phenomena like the famous handprints of Cueva de las Manos in Argentina (around 7.300 BC!), the stone stele forests of Ancient China, the practice of seal carving or the traditional woodblock printing of textiles in West Africa – for as long as we have had ideas, we have been searching for ways of recording and reproducing them. However, the history of the print as a multioriginal work of fine art is a slightly shorter one. First developed in China around 1400, the practice of transferring images from a matrix onto paper was a turning point in the democratisation of fine arts, making the image widely available and affordable for the general public.

We have come a long way in these six centuries of carving, engraving, etching, and rolling ink. Each epoque had its own set of demands – prints had to be colourful and accessible, intricate and narrative, outspoken and engaged, easily distributed propaganda materials, or highly sophisticated limited editions – all depending on the particular social and political circumstances.

What was at one point a revolutionary technique devoted to bringing art to the masses, would turn into an outdated, expensive practice as soon as the new, more lucrative option was discovered. Woodcut was abandoned due to its limited number of impressions, lithography due to the complexity of the process and discovery of offset printing, silkscreen was no longer the most versatile once digital printing became widespread, and so on. And yet, now that the digital era has brought us countless possibilities for creating complex and captivating images in infinite numbers, the act of hand printing a small batch of linocuts has become almost subversive.

While the need and/or value of using traditional printmaking techniques may not be obvious to everyone, almost all of them are present in contemporary art practices, as well as a wide array of mixed media and experiments in the expanded field of printmaking. Some of the categories this overview will be covering are:

- Relief printing (woodcut, linocut)

- Intaglio (engraving, etching, aquatint, mezzotint, drypoint)

- Silkscreen printing (also known as screen printing or serigraphy)

- Surface printing (lithography, photo-lithography, offset printing)

In many ways, the stories of each of these techniques are closely related to the political and societal issues which coincided with their discovery and wider use. Times of turmoil and crises have produced strong artistic movements throughout history, and more often than not, printmaking played an important role in both political propaganda and different forms of protest and activism.

The generative capacity and lucidity of this art form make it a great tool for artists (and governments) to express and distribute their political views and criticisms of social issues. This is why they were, and still are, widely used in anti-war movements across the globe, the Feminist and Civil Rights Movements, environmental activism, as well as various political campaigns.

Table of Contents

Woodcut – From a Traditional Technique to Political Statement

Asia

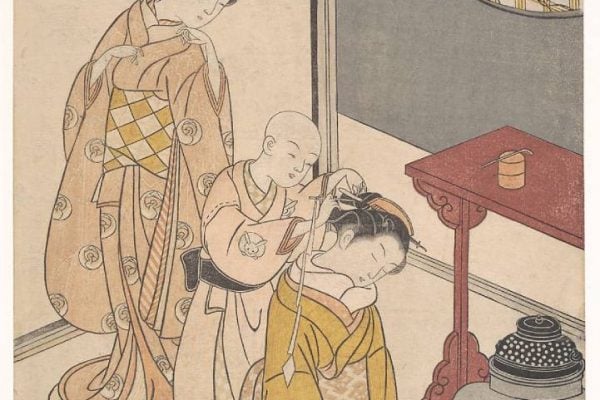

Printmaking as an official art form made its first appearance in East Asia, primarily as a means of spreading religious imagery across China. Typically, these were linear, narrative depictions of Buddhist scriptures (in a way, similar in intent to the early engravings representing Biblical stories in Central and Western Europe). Soon after, colourful representations of daily life became very popular and woodcuts could be found in people’s homes. The most sophisticated and well-known of these are the 17th and 18th-century Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.

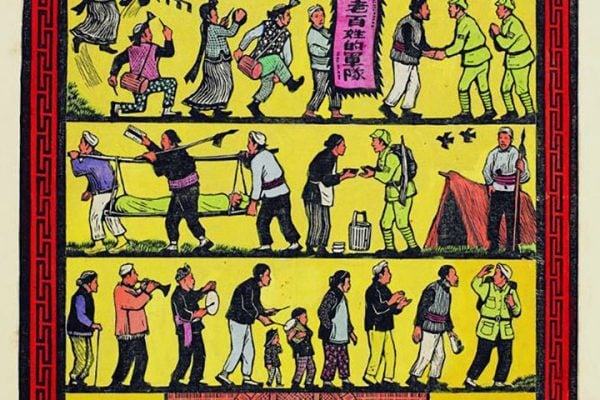

Interestingly, this was the exact style that greatly influenced the European Modernists, who later shaped the Asian academic art scene of the 19th and early 20th century. It wasn’t until after the revolution in 1911 that the full political potential of Chinese woodcut was unleashed. The traditional technique was now seen as a powerful tool for spreading leftist ideas and representing the people, as one of the dominant figures of this moment, Lu Xun, inspired the forming of the New Woodcut Movement. He believed that contemporary art needed to address the burning issues of the time, namely the ongoing Sino-Japanese wars, the needs of the working class, and the relationships between the Communist Party and its foreign friends.

During the 1930s and 1940s, at the time of the Second Sino-Japanese War, woodcut was fully accepted as a form of propaganda art by the majority of Chinese artists, while still maintaining a degree of liberty in terms of style and sources of inspiration. Influences were taken not only from the national culture, but also from the dark anti-war prints of European artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, Frans Masereel, and George Grosz. This was no longer the case once the CCP came to power, and brought some of the most rigorous demands of art, particularly in the time of the Cultural Revolution.

Europe

The Age of Extremes in Europe created a demand for socially engaged art, leading many modernist artists to abandon their research in the theory of form, light, and perspective, and take a firm stance against the violence and destruction of WWI. Like many of their contemporaries, artists were drafted and occasionally voluntarily enlisted. In the very beginning, the war was expected to end within a few months and considered in a tone of patriotism and optimism. Many artists showed their support for the cause by publishing works in periodicals like the Kriegzeit, but as the battles progressed, most started depicting the dark and violent sights of combat and destruction. By 1916, the publisher of Kriegzeit replaced the journal with Der Bilderman, a new publication advocating peace.

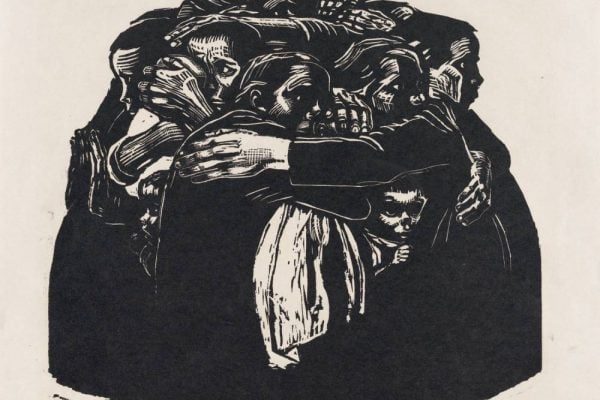

Some of the most captivating and engaging woodcuts that came out of this period are the black-and-white portfolios of Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). The artist depicted scenes of trauma and suffering of civilians and soldiers on various German battlefields in a manner that’s powerfully objective, yet sincerely compassionate and caring. Perhaps one of the most well-known works is her series War, and the woodcut representing the mothers of fallen soldiers. Kollwitz’s son died on a Belgian battlefield in 1914, at the age of 18.

Her Belgian contemporary, Franz Masereel, was one of the few artists who expressed an unequivocal disdain towards nationalism and warfare from the very beginning. Masereel’s woodcuts were printed in many anti-war books, portfolios, and publications, and greatly contributed to the anti-militaristic stance of European artists.

Socialist Woodcuts of Yugoslavia and the USSR

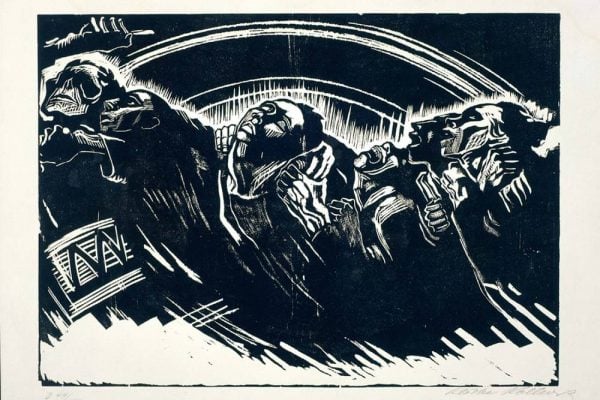

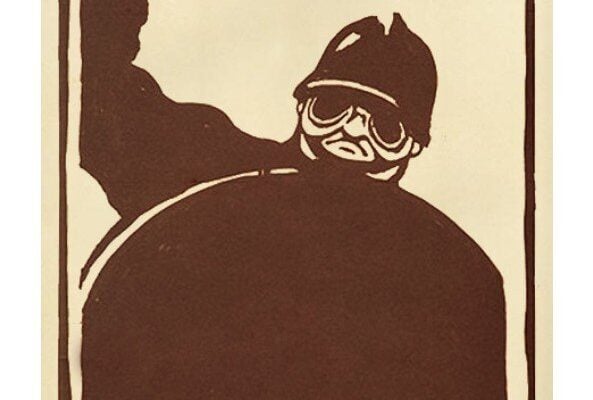

Greatly inspired by the October Revolution (1917), Yugoslav and Soviet artists saw it as their duty to use their art to promote revolutionary ideas, leftist and Marxist values and give voice to the proletariat.

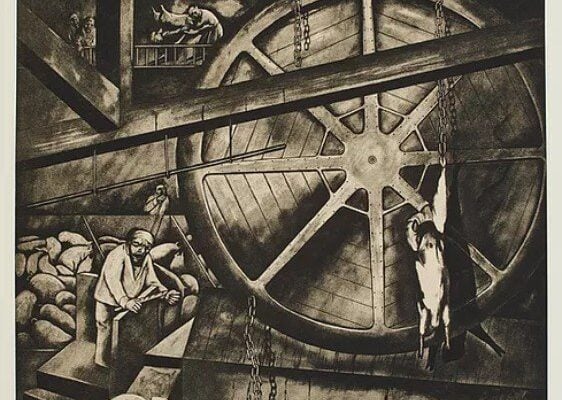

Black-and-white linocuts and woodcuts became an integral part of the revolutionary visual language due to their clarity and simplicity. Socialist realism was also seen as a reaction to the art for art’s sake approach of Parisian Modernism, and the majority of artists addressed issues related to the position of the working class, the economic crisis, and inequalities in society.

The leading Yugoslav printmakers of the time were Krsto Hegedušić, Đorđe Andrejević-Kun, Pivo Karamatijević, and others. Some of the most famous woodcuts of Russian revolutionary art were those of Nikolai Kupreianov, Vasilii Masiutin, Vadim Falileev, and Aleksei Kravchenko. Falileev, who was an active printmaker even before the Revolution, famously introduced coloured linocut to the Russian printmaking scene.

Latin America

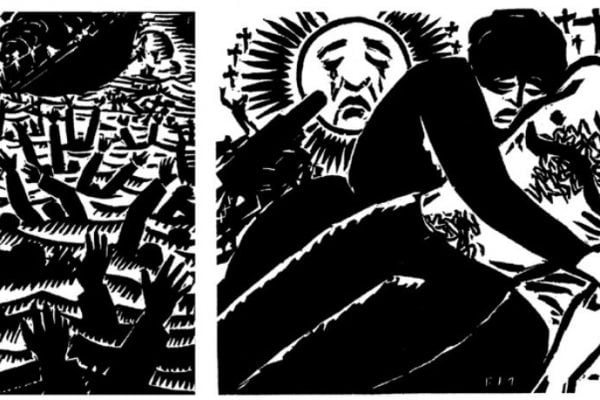

The history of social art in Latin America is vitally associated with the Mexican revolution (1910-1920), and famous left-wing artists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, as well as the printmakers David Alfaro Siqueiros, Xavier Guerrero, Manuel Manilla, and José Guadalupe Posada. Posada is considered by many to be the father of Mexican printmaking and is most widely known for his lithographs. Guerrero and Siqueiros published many of their woodcuts in the paper El Machete, which they founded as a left-wing publication alongside Diego Rivera.

In 1937, a printmaking collective called Taller de Gráfica Popular was established in Mexico City, by three communist artists who wished to abandon mural painting as the main art form of revolutionary thought – Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, and Pablo O’Higgins. The collective was not just a means of disseminating revolutionary ideas through printmaking, but its members were very much directly involved in the political context. David Alfaro Siqueiros was a guest member of the TGP when he famously attempted to assassinate Leon Trotsky in 1940, three years after the latter arrived in Mexico. After the failed attempt, printmaker Antonio Pujol was imprisoned, and Siqueiros fled the country.

While the Mexican artists are considered to have been most influential, it is important to note the other prominent figures in South American political printmaking, such as Carlos Mérida from Guatemala, and Luis Peñalver Collazo from Cuba, whose detailed large-scale woodcuts represented the Cuban people’s struggles against US oppression.

Intaglio and Battlefield Testimonials

The opposite of relief printing, intaglio is an umbrella term for a number of techniques involving making an incision into a plate of copper, zinc, or similar material. Outside of the fine arts, one of the most well-known applications of intaglio was in the printing of banknotes. The most notable techniques, etching, engraving, and aquatint, were famously used by artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Albrecht Dürer, sculptor Henry Moore, as well as Pablo Picasso. However, in terms of socially engaged printmaking, the most prominent figure in the history of intaglio was Francisco Goya.

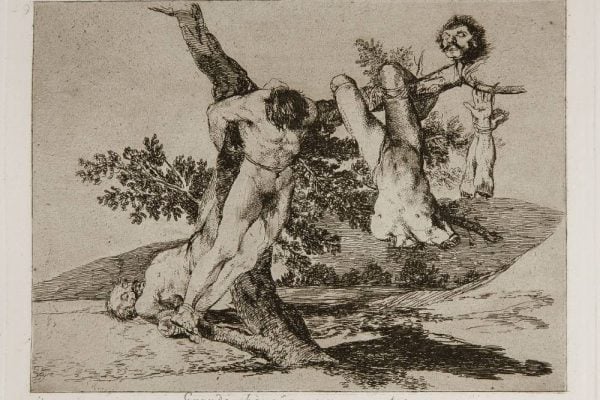

Goya created a large body of works during his lifetime, from portraiture, printmaking portfolios representing folk culture and fantastical beings, to works dealing with mental instability and psychosis, but his most famous series is one published posthumously, entitled The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra). The 82 sheets cover the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon’s occupation of Spain, and the Peninsular War (1808-1814). Some of the events depicted in the etchings are the most gruesome in Spanish history. Unlike the galvanizing effect of woodcut and linocut, the subtle values of intaglio allowed for a more objective testimonial of the cruelties and irreparable consequences of armed conflict.

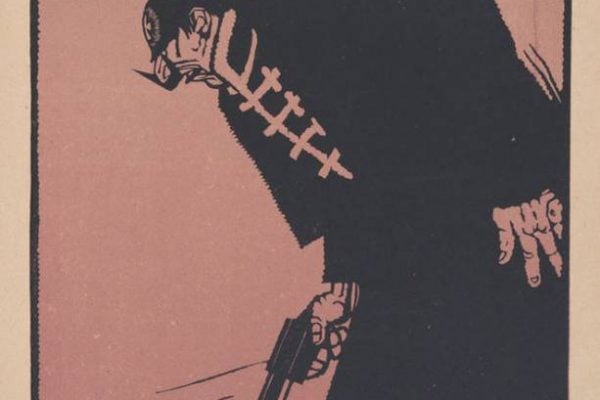

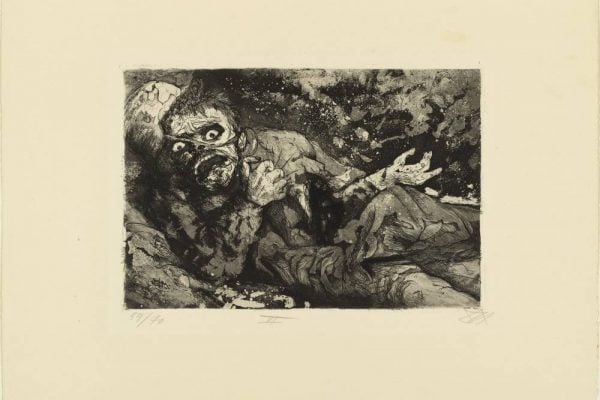

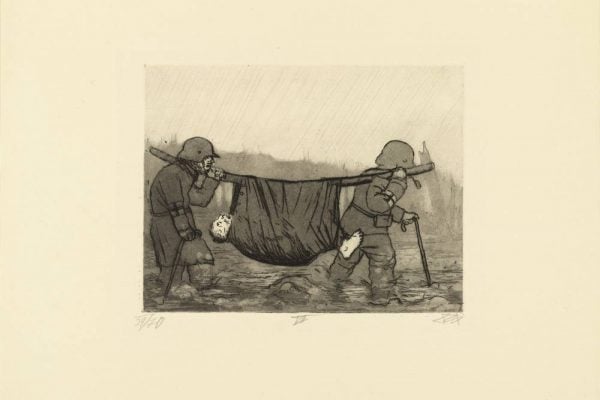

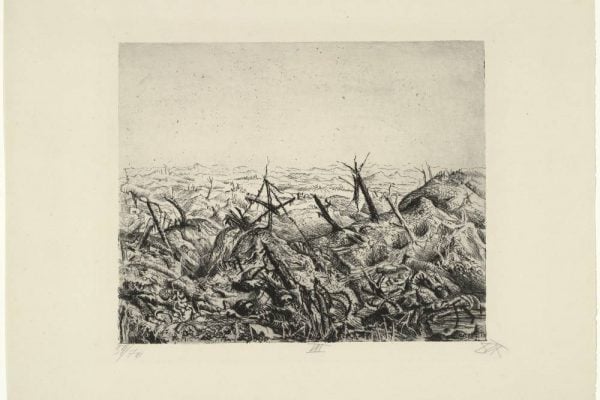

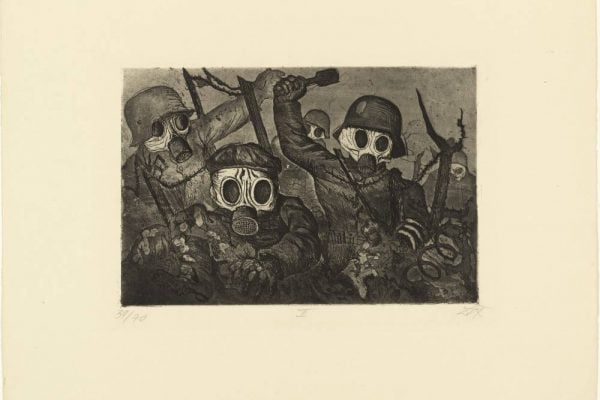

Almost a century later, Otto Dix and George Grosz, countrymen and contemporaries of Käthe Kollwitz, used intaglio to express the same antimilitaristic sentiments of both her and Goya. Dix, who like many other artists welcomed WWI with a sense of patriotic duty and enthusiasm in the beginning, went on to become one of the leading printmakers advocating against nationalism and aggression, having served the entire duration of the war. Many of his works were later unfortunately destroyed by the Nazi propaganda ministry, but the etchings and aquatints that survived vividly represent the death, suffering, and carnage he witnessed on the Western front. George Grosz, who famously changed the spelling of his name to express his loathing of German nationalism, created linear caricatures of German political figures and the military.

Lithography and its Role in Political Caricature

Lithography is a relatively young printmaking technique, developed towards the end of the 18th century. It belongs to the surface printing group, based on a simple, yet delicate chemical process, which is why it is one of the techniques many artists most commonly entrusted masters and artisans with, instead of personally controlling the whole process. It is, however, one of the most versatile as it can be used to reproduce linear drawings, ink wash, text, and photographs in large, multicolored editions.

Honoré Daumier, the French realist painter and master of satirical lithography, created over 6,000 original caricatures which he published in various newspapers. His paintings and lithographs expressed a critical understanding of the 19th-century political context in Europe – the poverty and social inequality, and the unjust distribution of power between the working classes and bourgeoisie.

José Guadalupe Posada, the Mexican artist known for creating one of the most famous images connected to Dia de Muertos, used lithography in a way very similar to that of Daumier. Posada used lithography, text, humour, and satire as a means of political criticism and greatly influenced many Latin American artists during and after the Mexican revolution. He didn’t live to see the end of the Revolution and the benefits of the cause to which he devoted his life and artwork.

Several artists who were not primarily printmakers, such as Pablo Picasso, Eduard Manet, and others, also created important bodies of anti-war lithographs with the help of printmaking studio professionals.

Screen Printing in the Sixties – Pop-culture and Protest

Screenprinting, or serigraphy, gained popularity in the 1960s thanks to the works of Andy Warhol and various other pop artists. It has become more widely known and used than other techniques like intaglio and surface printing due to its versatility – it was one of the first fine art printmaking techniques that could be applied to various materials and surfaces, such as textile, PVC, merchandise, product labels, and signs.

In terms of political context, the sixties were certainly a time that called for different forms of mobilization, activism, and protest. Just as an example, a single year, 1968, marked the end of the Civil Rights Movement and the assassination of Martin Luther King in the US, the USSR invasion of Chechoslovakia and Prague Spring, the Educated Youth proclamation of Mao Zedong, the worldwide student protests of May 1968, the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, and many other events related to the Cold War and its proxy warfare.

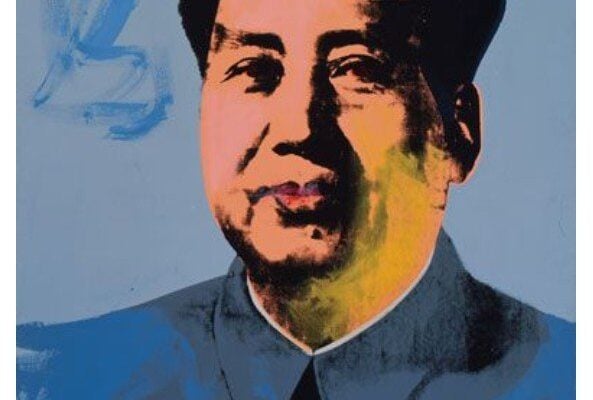

These events prompted many artists to raise their voices in protest, and silkscreen provided possibilities that were both easy to distribute, and in accord with the contemporary visual culture – the aesthetics of pop art, the vivid neon colours, and the use of text, collage, and photography. Andy Warhol famously depicted prominent political figures like Chairman Mao and Queen Elizabeth II, as well as created portraits for US political candidates’ campaigns.

In a more direct, activist approach to social art, Atelier Populaire in France brought together a group of art students and young artists who created many series of powerful political posters addressing issues around the student protests, their revolt against capitalism and US imperialism, solidarity with the working class, and the autonomy of European universities.

Contemporary Practices – New Responsibilities

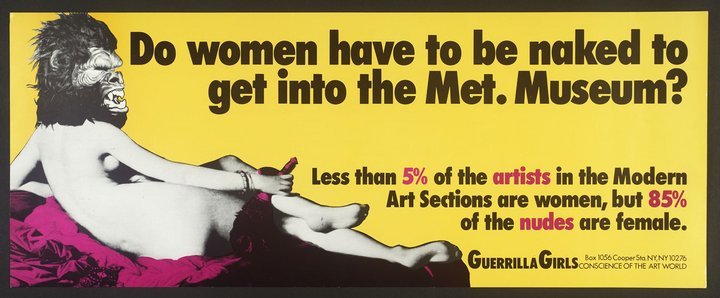

The artist movements of the 70s and 80s were all about moving on from object-based, institutional art towards dematerialized, conceptual and performance-based practices. In this context, printmaking typically remained in the confines of traditional art academies and institutions, but there are still some relevant examples of social printmaking from this period. One of them is surely the series created by the New York feminist group called The Guerrilla Girls, addressing the marginalized position of women artists in museums and galleries. Their original screenprint editions expressed facts and questions about the under-representation of women and people of colour in art history overviews, art shows, auctions, and publications.

The technological developments of the digital era saw a decline in the use of traditional printmaking techniques for mass-media purposes. However, many fine art printmakers continue to use them in their practices, both as a means for artistic exploration and experimentation, and within grass-roots organisations and alternative printmaking collectives. The direct physical contact with tools and materials has become imperative for those artists who are considering the new circumstances and global issues brought by the new millennium. Topics concerning animal rights, environmental protection, social justice, and their various intersectionalities with politics and identity are often addressed in the works of contemporary printmakers.

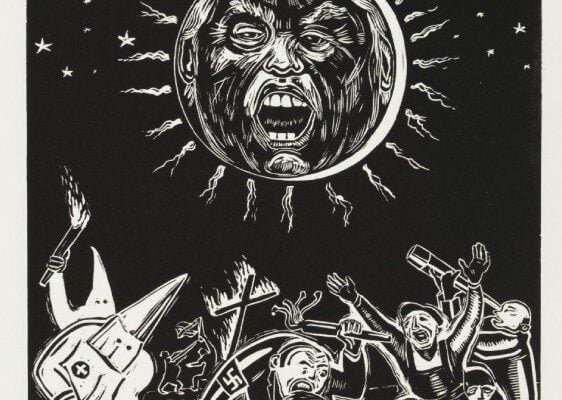

Sue Coe (1951) is an English printmaker and illustrator famous for her highly political linocuts which critique animal rights violations, the meat industry, fascism, and racism. The works are strongly influenced by the anti-war woodcut traditions of the early 20th century, while addressing present-day issues like veganism, neo-nazism, or the politics of Donald Trump.

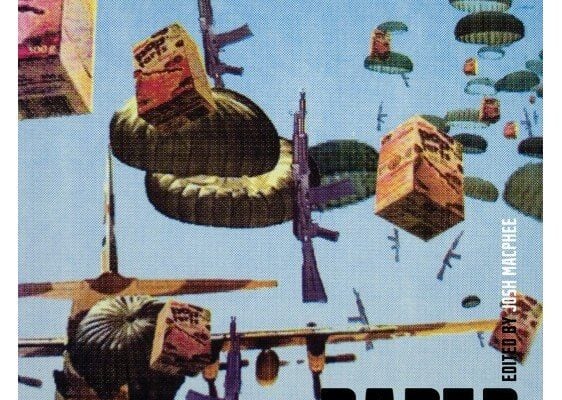

A younger-generation artist active in the field of social printmaking is the American printmaker Josh MacPhee, who founded the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative, and wrote Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today – an overview of various examples of protest art in printmaking history and current practices. Similarly to Sue Coe’s linocuts, his works demonstrate great insight into the histories of fine art and political protest, as well as a sense of social responsibility and empathy for the victims of wars, police brutality, discrimination, and human rights violations.

Calendonia Curry, also known as Swoon, is an American artist of the same generation, who combines printmaking and street art to engage the public in topics like climate crisis, violence, rehabilitation, and reintegration. Swoon is famous for her lifesize paste-up prints and site-specific installations, but she is also involved in many community-based projects, underlining an ethic of care in her practice. In general, the ideas of working from and within communities, respecting the environment, and researching local cultures are becoming more widespread in contemporary practices, as social art shifts towards a tone of healing and empathy.

Many up-and-coming fine art printmakers with revolutionary voices deserving of being included in this overview are yet to be represented and written about in the media, but we encourage looking into some of the more democratic and open sources of information available to us thanks to some of the nicer technological developments, as well as further research through some of the resources and links provided below.

References and Further Reading:

- Blanuša, Mišela – “Socijalna grafika: Između propagande i likovnog izraza”, Belgrade, 2011

- Cunningham, Eldon L, “Printmaking A Primary Form of Expression” (1992)

- Gale, Collin – “Practical Printmaking” (2009)

- Hardin, Andrew Joseph, “New Deal printmaking: politics and protest.” (2010).

- Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 575.

- Jule, Walter – “Precarious Balance”, Print Voice II (1990)

- MacPhee, Josh, “Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today“, PM Press (2009)

- Pogue, Dwight – “Printmaking Revolution” (2012)

If you feel inspired by our article and are eager to try your hand at creating your own prints, why not get started with one of our carefully curated printmaking kits? Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced artist, we have the perfect set to help you bring your creative vision to life. Explore our range and find the ideal tools to embark on your printmaking journey.

FAQ: Historical Role of Printmaking

Question: What significant role did printmaking play in the art of the period?

Answer: Printmaking played a crucial role in the art of its time by democratising access to images and information. It allowed for the mass production and distribution of artworks, making art more accessible to a wider audience beyond the elite class. This dissemination of visual culture contributed to the spread of artistic styles and ideas across different regions. Printmaking also enabled artists to experiment with new techniques and collaborate with publishers and patrons, fostering innovation and creativity. Additionally, printmaking played an educational role, as illustrated books and prints were used to disseminate scientific knowledge, religious texts, and political ideas. Overall, printmaking significantly influenced the cultural and intellectual landscape of the period, shaping the development of both art and society.

Question: What effect did printmaking have on illustrators?

Answer: Printmaking had a profound effect on illustrators, fundamentally transforming the way illustrations were produced and disseminated. The ability to create multiple copies of an image allowed illustrators to reach a broader audience and distribute their work more widely. Printmaking also introduced new artistic techniques and styles, enriching the visual language available to illustrators. The precision and detail achievable through various printmaking methods, such as engraving and etching, elevated the quality and complexity of illustrations. Furthermore, printmaking facilitated collaborations between illustrators and publishers, leading to the proliferation of illustrated books, magazines, and prints, which played a significant role in the cultural and educational dissemination of the time.

Question: How did the use of printmaking change the world of art?

Answer: Printmaking forever altered the artistic landscape by enabling the reproduction of images in multiple copies, thereby making artworks far more accessible to a broader audience. Before its widespread adoption, original paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts could only be seen in the places where they were physically housed, limiting their impact to local patrons and connoisseurs. By contrast, printmaking allowed artists and publishers to create and disseminate prints and illustrated books on a large scale, transforming both the production and consumption of art. As these printed images circulated, they introduced new visual ideas and techniques to distant regions, igniting international artistic dialogue. Furthermore, collecting prints became increasingly popular among the middle classes, effectively “democratising” art by bringing it out of the exclusive purview of the elite. Hence, printmaking not only revolutionised the method of art reproduction but also nurtured a thriving exchange of styles and motifs, shaping the evolution of cultural and aesthetic practices worldwide.

Ηi there, just wanted to mention, I enjoyed this blog post.

It was helpful. Keep on posting!